Time Has Caught Up With Miles Davis’ Most Hated Album

by Marshall Bowden

Of all Miles Davis albums, On the Corner has continued to stand as the most controversial of all time. Part of that stems from the old ‘this ain’t jazz’ argument that all Davis releases from at least In a Silent Way on up were greeted with by the jazz community, but in many ways, this album was the line in the sand for many Davis fans.

Recorded and released in 1972, there was barely any acknowledgment of On the Corner as any kind of real musical achievement by the jazz mainstream. The album was treated as a kind of challenge by Davis to listeners, maybe even a smack in the face, a ‘fuck you’ to pretty much everyone, even those who had admired Davis’ electric work up to this point. Kind of the Metal Machine Music of the jazz world, which makes one wonder what these listeners made of subsequent Miles Davis albums such as Get Up With It and the double live sets Pangea and Agharta. Probably most of them had stopped listening by then.

Related: 8 Reasons Miles Davis is in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame

Only through the dual filters of hip-hop and electronica has Davis’ vision come into sharper focus. In addition, Bill Laswell’s reworking of Davis’ electronic work, including tracks from On the Corner, while not to everyone’s liking, made it easier for modern listeners to ‘hear’ the music by moving much of the clutter to the background.

Amazon | Spotify

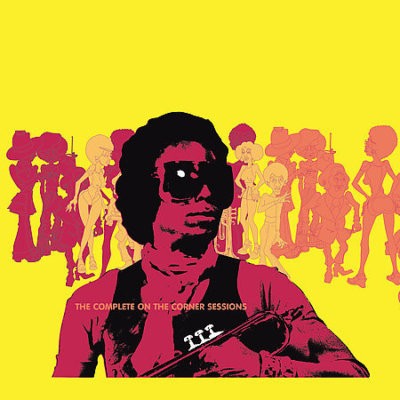

Columbia Legacy’s box set, The Complete On the Corner Sessions covers the music recorded during these sessions that span 1969-1972 and released on the albums On the Corner, Big Fun and Get Up With It. Big Fun was culled from a variety of material Columbia had in the vaults at the time, which was a lot, since Davis was recording constantly. Because of the editing that he and Teo Macero subjected the original session to in order to create a finished track, there was a massive amount of music that went unreleased.

Big Fun includes material recorded in the months after Bitches Brew was released, music recorded during the On the Corner sessions, and one track, “Go Ahead John,” which was done during the Jack Johnson Sessions. Get Up With It collected material recorded from 1970-1974, and every track from that album is included here with the exception of “Honky Tonk,” which was included on The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions.

MILES AND THE AFRICAN-AMERICAN COMMUNITY

This was a tumultuous time for the United States, poised between the Vietnam and post-Watergate eras, and for African-Americans in particular. Through disciplined exercises in civil disobedience, spirituality, unity, and outright militancy, black people had made more progress in a short time than ever before in American history. That led to the inevitable frustration at the barriers that remained, that refused to yield. While there were a few outbreaks of violence in the wake of this anger, much of it was channeled into community activism and the arts.

Sign up today for New Directions In Music Newsletter. It’s free, it’s got more info about music you love and it’s not full of advertising and other shit.

As a musical leader and a respected artist, Miles Davis felt that he needed to expand his audience within the young black community. These young people no longer listened to jazz, but they did listen to musicians such as James Brown and Sly Stone. It’s not hard to imagine that Davis felt he could be a positive influence on the lives of young black men and women in much the same way. He has said that he wanted to build a young black audience to join the young white audience he had gained with Bitches Brew and subsequent live concerts and to get out playing of the small jazz clubs that did not offer a chance to make enough money from performing live.

Like many longstanding musicians, Davis was beginning to learn that the key to continuing his career indefinitely was to continue to perform live on a regular basis. After his semi-retirement of 1975-1980, Davis would come to think of the albums as mere snapshot souvenirs of what he was doing at the time for fans to take home, while the real ‘meat’ of his musical development at the time was done in live performance. But at this time records were still important as a means of driving listeners into the concert hall.

In Davis’ autobiography, Miles, he talks about On the Corner being largely a product of the environment within black America at the time:

It was with Sly Stone and James Brown in mind that I went into the studio in June 1972 to record On the Corner. During that time everyone was dressing kind of ‘out street,’ you know, platform shoes that were yellow, and electric yellow at that; handkerchiefs around the neck, headbands, rawhide vests, and so on. Black women were wearing them real tight dresses that had their big butts sticking way out in the back. Everyone was listening to Sly and James Brown and trying at the same time to be cool like me. I was my own model, with a little bit of Sly and James Brown and the Last Poets. I wanted to videotape people coming into a concert who were wearing all those types of clothes, especially black people…”

(Miles: The Autobiography, by Miles Davis and Quincy Troupe, Simon & Schuster, 1989, p. 322).

Of course, Miles then immediately launches into his discussion of how he was influenced in the creation of this music by Karlheinz Stockhausen and Paul Buckmaster, and how Buckmaster stayed at Miles’ house during the sessions and had some influence over them. Buckmaster relates the tale differently, with most of his contributions being largely ignored by the musicians.

That’s what makes people find it hard to take Miles at face value; he enjoyed playing head games with people. But I think Miles hits strongly on the real inspirations and the exhilaration of the time, when black people in America were asserting themselves financially, in terms of fashion, in politics, in the entertainment world, and, as had long been the case, in music. In the 1970s more than ever, there was a mass realization of the fact that blues, jazz, r&b, soul, and rock, all rose from a small set of roots and were largely part of the same heritage, but had been broken into separate categories for separate audiences as a marketing scheme by the music industry.

In his introduction to Isaac Hayes’ performance at the Wattstax Festival (also held in 1972), Jesse Jackson said:” Today on this program you will hear gospel and rhythm and blues and jazz. All those are just labels. We know that music is music.” During this time music merged freely and without regard for genres and borders, with both profound and banal results. On the Corner, it is safe to say from this perspective in the next century, is among the more profound results.

THE SESSIONS

The Complete On the Corner Sessions starts off with the unedited master track of “On the Corner,” and it is something of a revelation, but not necessarily an obvious one. Because the music sounds, after all this time, not horribly weird or ‘out there.’ Which is to say that it apparently always made sense, but required a great deal of time and technological innovation to pass in order to sink in. Just like the album track, it drops us right in with the groove well in progress and Dave Leibman seeming to solo, at times butting up against John McLaughlin’s flying guitar work or Michael Henderson’s rock-solid bass.

There’s still a cluttered feeling to it, but it’s much clearer than before for the most part. One wonders if perhaps the Davis/Macero approach of using studio editing to shape and give structure to what had essentially been a jam session didn’t work against this music in some ways. Because this music essentially was, first and foremost, about the groove, and what went on top was interesting, but did not need to provide the signposts of melodic hooks or even real melody.

Ultimately, though, one can’t imagine the unedited thing being received more positively than the edited version. The unreleased “On the Corner (Take 4)” gives a glimpse into what might have been: the music is much looser and a lot less aggressive. Ultimately, Davis chose the harder-charging numbers to be edited into the On the Corner album. The music on Big Fun and Get Up With It is much more laid back at times, even while providing plenty of sonic activity. On the Corner may have been better received if it had mixed in some of this less hard-edged music, but that wasn’t the statement that Miles chose to make. In any event, this outtake is not only interesting, it’s good, with nice atmospherics, an open, expansive beat, and some nice McLaughlin guitar work.

Two other tracks here are from the same sessions, and provide complete versions of “One And One” and “Helen Butte/Mr. Freedom X,” part of the later edited tracks that appeared on On the Corner. Here there is more ebb and flow than was strictly allowed in the edited final tracks, and again, I’m not certain the edits worked to the best advantage of the music that was created. Still, I think that the final version of On the Corner that was assembled probably pretty accurately conveyed the vision that Miles wanted to convey with that record at that moment. Things were different quickly after those sessions and changed more fluidly on the live performances that followed the sessions.

Music recorded at sessions only a week from the original On the Corner sessions, “Jabali” and “Ife” are both more spacious and less aggressive than the music that was edited together for the album. “Ife” appeared on Big Fun, but “Jabali” remained unreleased.

Most of the rest of the music heard on this set, from Disc Two Track 2 through Disk 6 Track One, are either unreleased or were included on Get Up With It, which would be the last studio release from Miles Davis until his return in 1981 with The Man With The Horn. A lot of this music is more like the stuff Miles was playing live in 1973-74, with grooves that became increasingly Afro-centric, losing some of their rock music trappings.

Really striking is an unreleased track titled “Chieftain” from Disc two. This piece features a drum pattern that is really similar to what became known as ‘drum ‘n’ bass’ in the 1990s. The guitar work by Reggie Lucas creates a reggae feel that makes the piece feel a bit like dub as well. This is the Miles sound that musicians like Erik Truffaz or Palle Mikkelborg often seem to relate to.

“Rated X” is as challenging a listen as ever, with Miles’ organ clusters stomping all over the groove laid down by Cedric Lawson (electric piano), Reggie Lucas (guitar), Khalil Balakrishna (electric sitar), Michael Henderson (electric bass), Al Foster (drums), Badal Roy (tablas), and Mtume (congas, percussion). It’s hard to believe that this stuff was recorded only about three months after the actual On the Corner sessions, so completely different is the sound, the groove, and the intent behind this music. In many respects, On the Corner was an important turning point for Miles, one where he decided that since his music was unlikely to generate critical acclaim or huge sales, he simply accelerated his pace in the direction he wanted to go without regard for its reception.

Disc Three features one track from 1972, ‘Billie Preston’, which was included on Get Up With it; the rest of the material here is from 1973 and is unreleased. It does, however, provide insight into the way Miles was headed in his live performances. Until now, most of this type of thing could only be heard on the live releases Pangea and Agharta. A lot of the unreleased material here sounds pretty good and should be of interest to listeners who enjoy this period of Davis’ career.

Disc Four is a very meaty hour of music, both half hour tracks from Get Up With It. “Calypso Frelimo” is a heavy funk piece that many listeners still find to be repetitive and annoying, though it has many elements and solo work that is worth listening to.

The second track, “He Loved Him Madly,” a tribute to the recently-deceased Duke Ellington, is another matter entirely. This elegant, elegiac piece, full of mournfulness and space, is a raw representation of sadness and despair that ultimately becomes very spiritual. This is music that Miles recorded for no audience other than himself, and the result is both unexpectedly personal and hauntingly beautiful. Miles plays only organ, his trumpet fallen silent.

Guitarists Reggie Lucas and Pete Cosey create texture and some attempt at melodic interest, while Michael Henderson, Al Foster, and Mtume help to accent the underlying uncertainty of the piece. Although the piece cycles in and out of very small sections of more defined tempo, the piece is ultimately a thirty two minute solemn meditation on Ellington, Davis, life and death, and other cosmic mysteries.

Brian Eno declared this piece of music instrumental in inspiring his pursuit of the “ambient” musical aesthetic. “He Loved Him Madly” is a truly exciting and beautiful piece of music that is unique. It sounds like Miles staring into the abyss and not blinking or flinching.

Disc Five features music recorded in 1974 (except for the final track), with the first two tracks, “Mayisha” and “Mtume” both appearing on Get Up With It. There’s also an alternative take of “Mtume” that does little to shed new light on the piece. The three concluding tracks of this disc represent the last studio material Miles recorded before he went into retirement. “Hip Skip” is a mellow funk shuffle with outrageous guitar by Dominique Gaumont, with Pete Cosey on drums (!)

”What They Do” is the same group, with two guitars and Al Foster on drums. It’s incendiary, to say the least. The final track is the cool soul of “Minnie,” said to be inspired by Minnie Ripperton’s “Loving You.” It seems cliché to point to the mellow groove here as evidence of where Miles would go when he returned in the early 1980s, but ultimately I think Miles had no idea where he would go in the future. I think he believed there would be a future, and there very nearly wasn’t. It was probably smart for Miles to sit out the next five years; when he returned the music business had changed, and he seemed to grasp that. Had Miles not stopped playing in 1974, he may not have survived another year.

The final disc contains the oddity “Red China Blues” (again from Get Up With It), followed by the final album version of On the Corner in its entirety. The two other tracks are 45-rpm edits of the track “Big Fun/Holly-wuud” found on Disc Three.

I’m sure there will be some reservations about Columbia combining all these various sessions under the On the Corner banner. There are a wealth of different groups here, with different sounds and a wealth of music here created with different visions and intent.

But, first of all, Columbia showed that they would work in this manner when they included sessions which came later than Bitches Brew on the Complete Bitches Brew Sessions box. There was no other legitimate home for some of these unreleased tracks nor those that were used, in edited form, on albums such as Big Fun, Circle In the Round, or Live-Evil. And here again, what else would they have done? Release a Get Up With It complete sessions box?

I guess many fans would love to see a total 1973-1975 bands package that mixed both studio and live material, but that is not anything like the way the rest of the Miles Davis box series is arranged. The Complete On the Corner Sessions is a major release that offers a great deal of insight into what Miles was doing from 1972-1974. Not sure what’s to follow (Agharta/Pangea box? Live unreleased recordings of the 73-74 bands, if there are tapes that aren’t known about currently? How will Columbia deal with Davis’ legacy with the label from 1981-1985.?), but the Davis box sets stand as one of the crowning achievements of modern jazz reissues/remasters. Davis recorded himself and his bands tirelessly, and listeners have become the beneficiaries of all the music that has remained stashed in the vaults previously.

If Miles were alive, he might consider this music as ‘old hat’ as “So What.” But for the rest of us, it’s not so much a look back in time as a look at what it took this much time for most of us to catch up with.

As a listener who collected these records as they were released, their soundscapes were endlessly fascinating to hear on multiple levels. Detroit bassist Michael Henderson was a key factor in virtually all this music at pivoting the rhythm in a very new and funky direction. Adding East Indian and African percussionists gave this music an exotic density that was every bit as funky as James Brown and Sly Stone but also offered additional complexity to tune into and identify. I immersed myself deeply in all of these recordings when they were first issued during my teenage years. I have committed so much of what it offers to aural memory at this point (Miles DOES eventually gravitate to trumpet toward the climactic portion of “He Loved Him Madly” but hear the two guitarists playing in tandem while Miles is laying down the funereal atmosphere that permeates the piece/peace with his electric organ! Perhaps it’s not “Jazz” but it’s certainly inspired by DUKE. BTW, I stopped listening to deceased musicians years ago and try to keep an ear slanted toward “What’s New?”