History of Jazz: Part 4

Bebop arrived on the scene, to hear the tale, a fully formed grotesque of music, a deranged Athena fully sprung from the head of the Zeus-like swing era. It caused some musicians, such as Cab Calloway and Tommy Dorsey, to have violent reactions. Many audiences weren’t ready for the new sound either. This is what we commonly hear about one of the most important musical developments of the 20th century.

As usual, there is some truth to the stories but there is also a lot of overstatement. The fact is, Bop was more evolutionary than revolutionary, and might not have been seen as anything but the next logical progression if not for a couple of historic events that kept the incubating music under wraps, as well as the incendiary personalities of some of its leading musicians.

There can be no question that the style of big band music originated in Kansas City by performers such as Count Basie and Bennie Moten had largely been appropriated by a white, middle-class audience in the period just prior to and including World War II. In addition, the term “Swing” was commercialized and used as a marketing buzzword. Degan Pener points out in The Swing Book that the recording industry went from gross revenue of $2.5 million in 1932 to $36 million in 1939, largely due to the popularity of swing music.

This type of thing has been common throughout American history; artistic, cultural, and lifestyle statements that are seen as threatening or perhaps a form of rebellion are incorporated into the mainstream through the commercialization of their iconography. Think of the sudden popularity of leather, vinyl, or “bondage” clothing, or the commercialization of teen “grunge” music and fashion in the 1990s.

Clearly, the pioneers of bebop were originals, not just musically but also original personalities who could not be appropriated or imitated at the time because they placed themselves well outside the mainstream. If society would not recognize black people’s artistic achievements, seeking instead to sanitize and assimilate the music that was born of the original African-Americans’ experiences in this country, then why should black musicians continue to function within the mainstream?

Still, the musicians who would finally usher the new sound of bop into being had their training in the bands and music of the swing era. Louis Armstrong had already begun to establish jazz as the music of the soloist, and the best swing soloists, like Lester Young, were continuing to experiment with ways to push the boundaries imposed on the soloist further. Young became adept at gliding forward with lengthy phrases that took no notice of the natural division of the bar line, which had been a problem for some earlier jazz soloists.

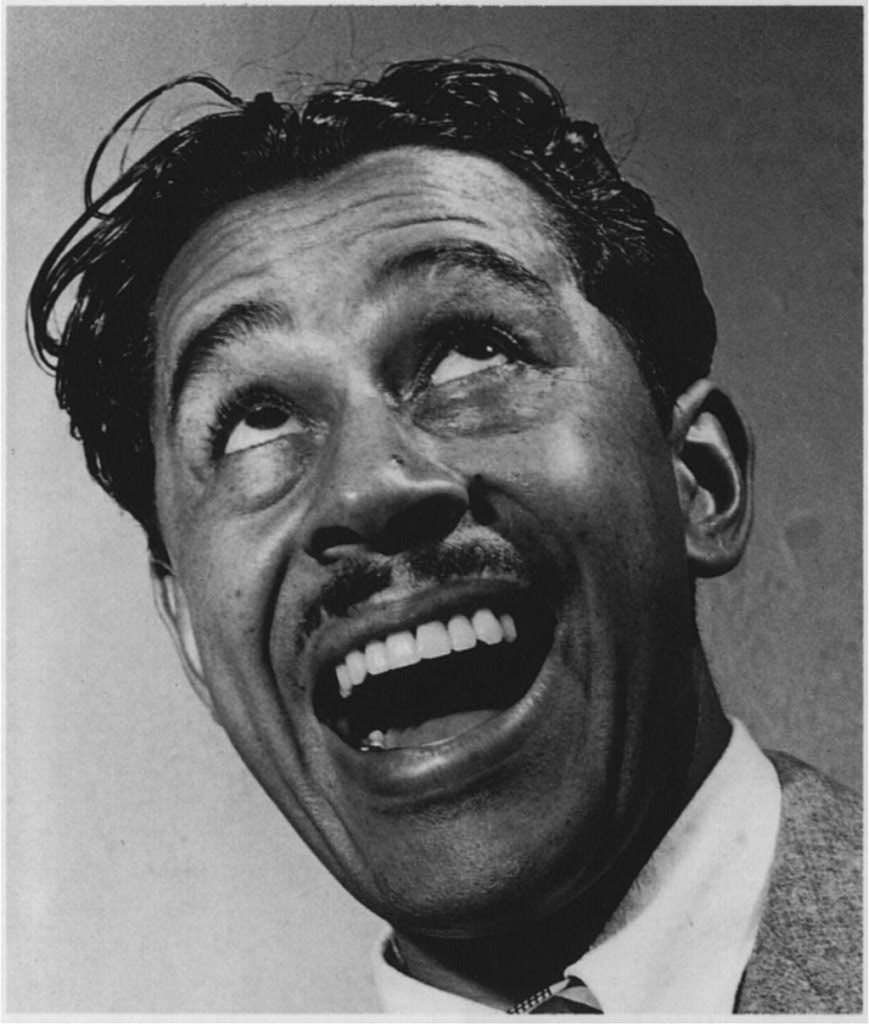

William Gottlieb Collection, Library of Cogress

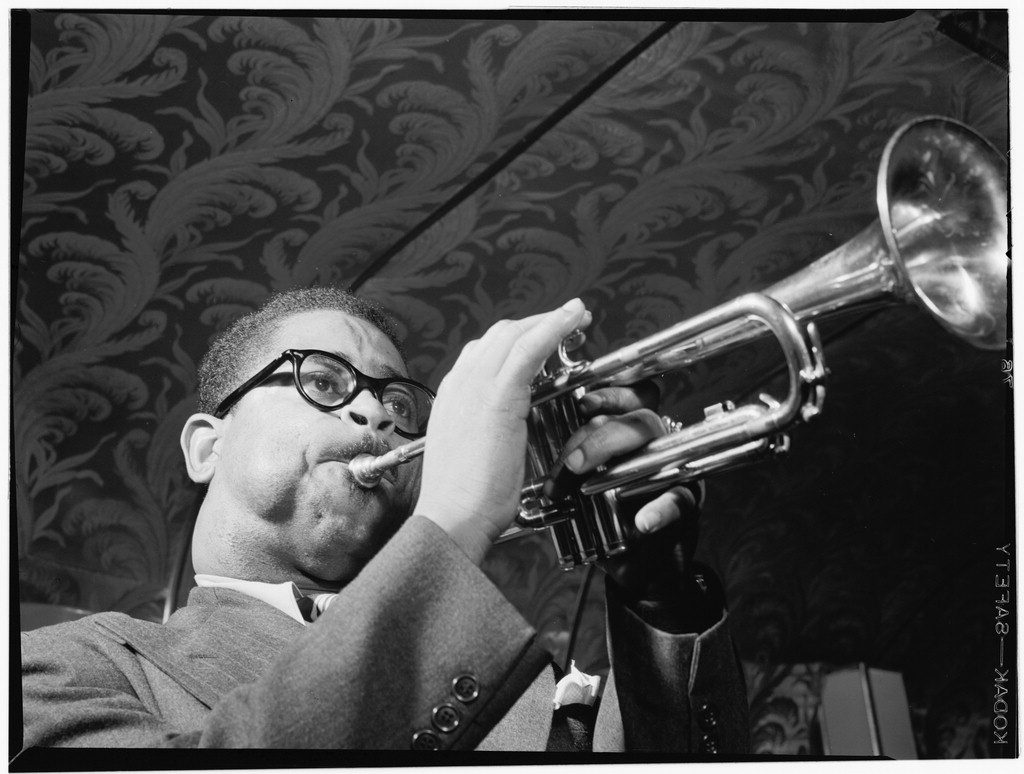

Charlie Parker certainly listened to and was influenced by Young, who, though he played within the idiom of the time, was himself outcast because he didn’t play tenor sax in the prevailing Coleman Hawkins style. Dizzy Gillespie cut his teeth in Cab Calloway’s band until his explosive solos caused Calloway to admonish him not to play “that Chinese music” in his presence.

Between 1941 and 1945, a number of bands had become incubators for the future “bop revolution”, none more auspicious than the group led by Earl “Fatha” Hines. Hines was a pioneering jazz pianist, well known as one of the fathers of the stride piano style, but he never ceased to be interested in the further development of jazz music and was capable of playing vital and even innovative piano solos into the 1970s and 80s. In 1943, Hines’ group included vocalists Billy Eckstine and Sarah Vaughn as well as horn players Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, and tenor man Wardell Gray. Gillespie composed his signature piece, “A Night In Tunisia” while still working with Hines. It was not only a bebop composition; it also was one of the first jazz compositions utilizing Afro-Cuban rhythms.

Unfortunately, this group did not record due to a strike by the American Federation of Musicians that prohibited recording by its members. Those fortunate enough to have heard this group play live heard, in all probability, the chrysalis of swing into what was becoming bebop, but that was really only a handful of people. What has been lost to history are recordings of Parker and Gillespie, in particular, honing the identities that would burst upon the jazz scene a short time later. The strike lasted more than a year, and when it was over Parker and Gillespie (along with Eckstine and Vaughn) had moved on, though Gray did remain with the Hines band through 1946.

Ironically, the same musicians’ strike and the ban on recording are also pointed to by many as a contributing factor in the demise of swing. By the time World War II ended for the United States, those returning from overseas had little reason to anticipate the complete change in the music scene that confronted them. Bebop was now widely, though by no means universally, accepted and the predominant form of jazz being performed and discussed with any degree of seriousness.

Early jazz and swing musicians looked upon themselves largely as entertainers. There was no comprehension that jazz music might be or develop into an art form. Even later, in the 1950s and 60s, those jazzmen who survived from this era were often embarrassed or pretended not to understand when the music was discussed or written about in a serious way. The bebop musicians did not feel this way at all. They refused to be relegated to the role of entertainer, often behaving in temperamental or “difficult” ways, often refusing to discuss their music with non-musicians, and sometimes even turning their backs on the audience. The entire attitude of bebop seemed to be “I am playing for myself and for the other musicians who are playing with me. Your listening is purely coincidental.”

William Gottlieb Collection, Library of Congress

Of course, most of these musicians did want their music heard and enjoyed. Charlie Parker grew depressed during a series of dates in California when the group’s music was greeted with outright hostility. It was 1945 and Parker was 25 years old; he would be dead within 10 years. His drug habit had become tellingly problematic by this time, and Parker decided to stay in Los Angeles and do some recordings for the small Dial label over a twenty-month period in order to earn some cash.

These recordings are among the treasures of the Parker canon, demonstrating his endless inventiveness as we hear several versions of each tune with solos that never seem to repeat themselves, tread overly familiar waters, or become rote. In fact, there is probably no better way to either introduce yourself to Parker’s genius or to dig deeper into it than to check out The Complete Savoy and Dial Studio Recordings 1944-48. Not only will you hear Parker at the height of his inventiveness and power, you will also experience bop musicians such as Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach, Bud Powell, Tommy Potter, and John Lewis providing some truly transcendent moments of their own.

What is truly amazing about the Dial sessions, especially in light of bebop’s well-deserved reputation as music of complex and labyrinthine chord changes, is that many of the tunes here are based on 12 or 32-bar blues. Parker seems to always find something new to say even within the familiar blues changes. Physically and emotionally Parker was hardly at his best when most of these sides were recorded, yet you’d never know it from the performances. These were indeed the golden years of bebop when the music and its chief proponents were mature, yet fresh and still full of ideas and excitement over what they had accomplished and would still do in the future.

From our vantage point, it may be difficult to imagine that this music created so much controversy or that its creators were not instantly hailed as geniuses by one and all. In many ways, bebop did create a break from jazz’s past, a dividing line that made it impossible to go back. But it is hard to imagine that bebop, or something like it, wasn’t inevitable as the next stage in the development of this music. There was simply too much talent, too much of the history of oppression, and too much personality in these young men for it not to have happened.

- Part 6: Hard Bop, Post Bop & Soul Jazz

- Part 5: Cool Jazz

- Part 4: The Bebop Revolution

- Part 3: Swing and the Big Band Era

- Part 2: Traditional Jazz & the Jazz Age

- Part 1: Blues, Ragtime and the Origins of Jazz