How the paths of Ramsey Lewis and Maurice White led to the recording of this quiet storm classic

by Marshall Bowden

Ramsey Lewis was one of the more popular jazz musicians of the 1950s and 1960s, bridging the gap between gospel, blues, soul, and jazz. The Lewis of this period is best known for his gospel and blues-inflected pop tunes with a heavy backbeat, such as “The ‘In’ Crowd”, “A Hard Day’s Night”, and “Hang On Sloopy”.

The Trio

The Ramsey Lewis Trio always included these popular songs in their repertoire, songs that could hook a crowd of largely non-jazz listeners, including a jazz version of the operatic “Carmen” and the dusky “Blues for the Night Owl”. While these garnered some airplay and made the R&B charts, the breakthrough was a recording of Dobie Gray’s “The ‘In’ Crowd” recorded live at The Bohemian Caverns in Washington, D.C. and released on The ‘In’ Crowd album. Between 1964 and 1972 Lewis placed 19 singles on the pop charts utilizing this style that he referred to as “jazz, R&B, pop and gospel all rolled into one.”

The Trio was awarded a Grammy for Best Instrumental Recording of 1965. Other hits in the same vein included “Since I Fell For You”, “A Hard Day’s Night”, “Something You Got”, “Hang on Sloopy”, and “High Heel Sneakers”. All of these songs utilize simple elements: well-worn blues riffs, a strong backbeat, plagal cadences, a party atmosphere provided by audiences who clap along, and familiar tunes. Harmonic sophistication and technical wizardry were not the points of these performances, as Lewis himself pointed out: “The most intricate chord in the whole thing, I think, is a seventh” he told Downbeat.

As so often happens, the success of the original Ramsey Lewis Trio brought about dissension and the group was unable to stay together, with “High Heel Sneakers” being their last chart success together. Lewis was looking for new trio members. He filled the bass spot with Cleveland Eaton and went looking around for a new drummer to fuel his Ramsey Lewis Trio 2.0.

It didn’t take long for him to hear about this new kid who was playing gigs as well as doing studio work and recording advertising jingles around town. Through hard work and a high level of professionalism this kid had managed to become a drummer of choice around Chicago at a time when all the major labels had studios in town. That kid was Maurice White.

Lewis ended up hiring White, beginning a profound relationship that lasted for years in an industry that can be all too cutthroat. To White, Ramsey was a real mentor who taught him about every aspect of being a professional musician–the business, travel arrangements, getting paid, self-care while on the road, appearance, and professionalism. Young Reece developed mightily as a musician as well, but it’s because he was open to learning so much outside the actual performance that he was able to move forward with his musical dreams.

Lewis encouraged the young drummer to continue to develop and expand on his drum work. One day White discovered a kalimba, or African thumb piano at a downtown Chicago music store, and he instantly bought one and started to experiment with it. Ramsey Lewis was excited about it and convinced Maurice to make it part of the Trio’s act. On the Trio’s 1969 album Another Voyage White played the instrument for the first time on a recording. The kalimba became an integral part of Earth Wind & Fire’s sound, figuring on a number of popular tracks, as well as in lyrics to songs like “Kalimba Story.”

Check out Mark Holdaway’s article Words About Maurice White’s Kalimba Playing at Kalimba Magic for a nice analysis of some of White’s work with the instrument

Despite his popularity, Lewis was frequently dismissed by the jazz cognoscenti as not serious jazz. It was a common complaint with musicians who mixed their jazz with soul and gospel and maybe a sprinkling of the new funk. Cannonball Adderley, Les McCann, and Rahsaan Roland Kirk were all top notch jazz artists who were written off by many at one time because they dared to make jazz popular music, as it once had been.

Lewis knew he had something, though. The new trio was able to repeat the previous trio’s success with recordings of Stevie Wonder’s “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)” and the gospel standard “Wade In the Water”. Subsequent albums featured soul numbers like Marvin Gaye’s “Ain’t That Peculiar” and “Tobacco Road”.

Dizzy Gillespie once commented that Lewis was, in fact, playing fusion music way ahead of the electronic experiments that the word conjures in most of our minds, and I don’t think Gillespie was too far off.

In 1969 White left the Ramsey Lewis Trio and headed west to begin building his new idea of a musical group. Earth Wind and Fire signed a deal with Warner Brothers Records and recorded two albums for the label before negotiating a new deal with Columbia Records, where Clive Davis was an early supporter and encouraged the signing of the band.

Head to the Sky & Funky Serenity

Head to the Sky was EWF’s second album for Columbia, and it started to gel in ways that suggested very strongly what the group was to become. The amalgam of jazz, rock, soul, doo-wop, gospel, and funk was coming together in a very meaningful way. Even if White’s lyrics were sometimes a little heavy-handed at this point the music was like something that was there, in the zeitgeist, but which hadn’t quite ever materialized before. The more belief that Maurice White and his increasingly balanced team of musicians poured into their songs the more they materialized, became less ethereal, though the whole thing was still like something out of a dream.

Described by Maurice White as “a declaration of the band’s personal and professional transformations” (Maurice White, My Life with Earth, Wind and Fire page 128) the album showcased the band’s musical diversity as well as its affinity for jazz fusion and Latin sounds,

“Their message is basically spiritual” wrote Vince Aleti in a Rolling Stone review at the time, “but if their lyrics are weak and, at times, awkward, the music and the voices-as-music are strong enough to convey that feeling with a minimum of words…The vocals are breathy and soothing without being too ethereal; altogether, they sound like a cosmic choir and generate a Sly Stone effect. At its best, the music is fluid and enveloping,”

“Yet the sound is never so spiritual that it isn’t firmly grounded — guitarist Johnny Graham, bass player Verdine White and drummer Ralph Johnson are particularly good.”

White’s vision for the group, which was based on the inclusiveness and groove of Sly and the Family Stone but was heavily influenced by the doo-wop he grew up with a well as the multiethnic vibe of a group like Santana, is closer to fruition on Head to the Sky, but the pieces aren’t quite in place yet. Nonetheless, the band plays really well, with a high level of sophistication.

In the meantime, White’s old mentor, Ramsey Lewis, was going through some changes as well. Lewis was an astute observer and because he had so many hit records, he was aware of the larger music world outside the jazz business. He saw, in the same way that Miles Davis and a lot of other jazz musicians did, that the music business had changed and that continuing to ply the same old formula that had worked for years was not going to cut it. Many musicians felt that they needed to update their sound and presentation or face becoming increasingly irrelevant.

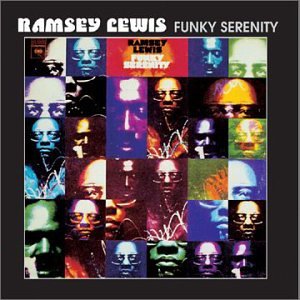

Lewis recorded an album titled Funky Serenity in 1973 that featured him mostly on Fender Rhodes electric piano and electric harpsichord, with his regular trio of bassist Cleveland Eaton and Morris Jennings. The album opens with the soul-funk Eddie Green composition “Kufanya Mapenzi (Making Love)” which is a complete analog to his more familiar trio work over the past decade. It features the same kind of backbeat and some funky bass work, while Lewis works the same kind of solo territory has he had on “In Crowd” or “High Heel Sneakers.”

The rest of the album moves restlessly between covers of contemporary R&B hits (“If Loving You Is Wrong”, “Betcha By Golly Wow,” “Where Is the Love”) and rock songs (“Nights In White Satin”). The originals are the most interesting, with the cool “Serene Funk” and the trippy but eventually groove-laden “Dreams” forming the heart of the album.

Funky Serenity is a grab bag of styles that sounds like a plugged-in Ramsey Lewis Trio album. Billboard’s music industry sheet, Radio Action & Pick LPs for February 24, 1973, lists the album as a recommended jazz pick, commenting: “Impressively wide range of electric and concert keyboard stylings from a jazz-pop giant.”

Enter Charles Stepney

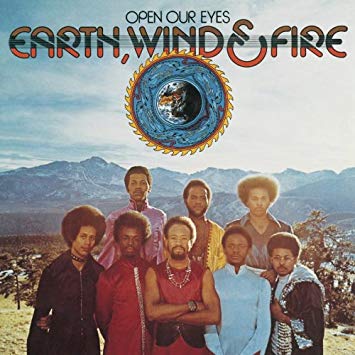

EWF’s third Columbia album, Open Our Eyes, is the band’s breakthrough recording. The concept of EWF as more than just a band, but as something of a traveling revival show, was coalescing as the group’s personnel stabilized into the classic EWF lineup:

Philip Bailey – Vocals, Congas, Percussion, Larry Dunn – Moog Synthesizer, Piano, Organ Johnny Graham – Guitar, Percussion, Ralph Johnson – Drums, Percussion, Al McKay – Vocals, Guitar, Percussion, Maurice White – Vocals, Drums, Kalimba, Verdine White – Vocals, Bass, Percussion, Andrew Woolfolk – Soprano Saxophone, Flute

In addition, White was writing some better lyrics, and the band was as tight as it had ever been. Head to the Sky had sold well enough for the group to be a priority at Columbia Records, even with the departure of Clive Davis.

To take the band to the next level, White brought in someone from his Chicago past to help him as an associate producer and musical arranger–Charles Stepney. During his time as a Chess Records session man, White had worked with Stepney and recognized his immense talent.

Stepney had been a staff arranger/producer at Chess and its Cadet subsidiaries, and he had worked extensively with Ramsey Lewis during the period when White was with the Trio. In this capacity, he recorded a series of albums with Lewis as well as recordings by Muddy Waters, Marlena Shaw, and Phil Upchurch, among others.

Stepney was also musical director and producer of the group Rotary Connection, a musically influential group that included then unknown vocalist Minnie Riperton. His string arrangements are among the most distinctive in popular music, along with those of Paul Buckminster. In addition, he brought in many top studio players from the Chess/Cadet roster as guests. Among those who contributed to the band’s records are Phil Upchurch, Pete Cosey, and Bobby Christian.

White had always wanted to work with Stepney again and now, with the stability afforded by a couple of decently selling records, that was a possibility. Stepney was able to bring the best out of each musician, including White, and his arrangements laid the cornerstone for the definitive EWF sound. A simple track like “Feeling Blue” got a new shimmer as Stepney played off Philip Bailey’s high vocal harmonies against woodwind player Andrew Woofolk’s soprano sax and flute.

Aleti is right in mentioning the idea of “voices-as-music” in his review of Head to the Sky, as the band was starting to work with basically instrumental pieces which had only syllables as lyrics, as on the track “Caribou.” Philip Bailey had a real knack for singing this kind of song, and such compositions, or sometimes fragments of songs without words became a part of the group’s ongoing work both on record and onstage. Their first two Columbia albums had featured instrumentals with vocalese and it would be heard in future tracks like the well known “Beijo” Brazilian Interlude.

At the same time, the group was never far from laying down a powerful groove that kept the whole affair from veering off into hippie psychedelia on tracks like “Kalimba Story’ and the opener, “Mighty Mighty”.

As EWF was taking off in a big way, Ramsey Lewis followed Funky Serenity with the album Solar Wind. Produced by Steve Cropper who also contributes his trademark guitar work, the album combined some sharp trio numbers featuring Ramsey on acoustic piano with charts on some recent pop hits (“Hummingbird,” “Summer Breeze”, “Come Down In Time”) with electric piano and touches of synthesizer. It;s a more focused album than Funky Serenity, but it also seems less experimental and open, more conservative.

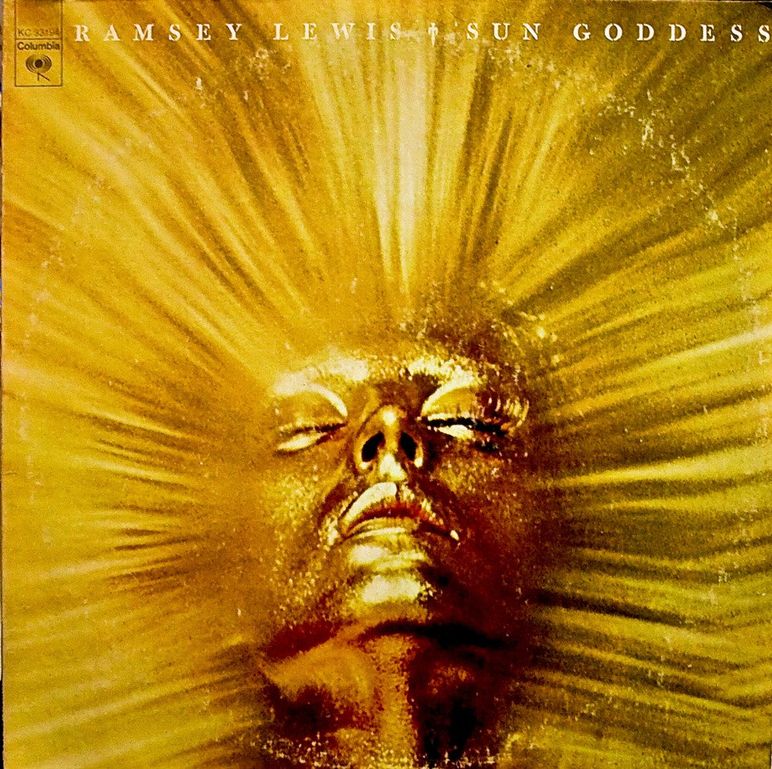

Sun Goddess

According to Maurice White’s autobiography, the EWF tracks that ended up on Ramsey Lewis’ Sun Goddess album were the result of some EWF studio sessions done in June of 1974:

“A couple of the tracks we had recorded I knew we were not going to use, but I thought they could be great instrumentals. I was really excited about a thing called “Hot Dawgit.” (p. 159)

White called Lewis, who was also working on tracks for a new album. The two agreed on a time frame and Maurice, along with brother Verdine, vocalist Philip Bailey and guitarist Johnny Graham flew to Chicago and Paul Serrano’s studio, situated in a brownstone.

The group recorded “Hot Dawgit,” and though it took several takes and some tempo changes to get it to feel right, the track was eventually laid down and everyone was pleased with it.

Almost as an afterthought, White mentioned the other track he had. He explained that it was a nice little groove for soloing with a Latin vibe, but it wasn’t going to be a single like “Hot Dawgit.” And so the group cut the untitled track, which Maurice later dubbed “Sun Goddess.” White called Don Myrick, a local sax player he knew, to come over and solo over the track, and of course, Ramsey also soloed on the Fender Rhodes, effortlessly gliding over the EWF rhythm section,

All that was left was for Maurice and Philip Bailey to overdub some percussion and some of those wordless vocals that were a signature sound of EWF. The entire track clocked in at around eight minutes–definitely not the length for radio play. But it became the album’s title and leadoff track.

“Hot Dawgit” was released as the album’s first single, and the response was completely underwhelming. White was disappointed, as he had sold the track to Lewis as a surefire hit. But black radio stations in major U.S. markets had started to play “Sun Goddess” despite its length. The track was hugely popular with listeners, who began to appear at record stores asking for the album hat included “Sun Goddess.”

The album is a good one, more cohesive than Funky Serenity but less constrained than Solar Wind. There is a really fine cover of Stevie Wonder’s “Living For the City”, a song that was widely covered by small jazz combos and big bands alike.

There are four Ramsey Lewis penned tracks. “Love Song” is lush and showcases Lewis on both acoustic and electric piano. The track has both the smoothness of the Philadelphia soul sound and the hard-edged soul jazz of Lewis’ earlier work. “Jungle Strut” is a straightforward funk tune that works pretty well. “Tambura is a short but sweet strut, and “Gemini Rising” settles, after an atmospheric introduction, into an affable swing shuffle that provides solo space for Cleveland Eaton’s bass.

And “Hot Dawgit,” the instrumental track that Maurice White was so sure would be a hit? It’s not bad, a catchy little soul pop thing with wordless vocals of the ‘la la la’ variety. But in retrospect, it’s difficult to see how White was so excited about the track and how both White and Lewis missed the idea that “Sun Goddess” was a shimmering gem of a quiet storm anthem.

But it was. Sun Goddess, the album, hit Number 1 on the Billboard R&B and Jazz charts, and Number 12 on the Pop charts. Very few jazz-oriented musicians were selling records on that level. It became a permanent part of Lewis’ live performances, and in 2011 he re-recorded several tracks from the album and did a retro tour with it as well.

Earth Wind and Fire performed the song on their 1975 tour in support of their That’s the Way of the World album, and a representative recording of it can be heard on the group’s (mostly) live album Gratitude. The group has continued to perform versions of the song at their live shows up to the present day.

After Sun Goddess

As previously mentioned, EWF spent 1975 promoting That’s the Way of the World and touring. They also recorded a handful of studio tracks, including the hit “Sing a Song” for the fourth side of the Gratitude album.

Charles Stepney continued to work extensively with EWF until his untimely death in 1976 at the age of 43. In fact, the vaunted musician, composer, arranger, and producer was more in demand than ever following his work on Open Our Eyes and That’s the Way of the World. The year he died he had completed Deniece Williams’ debut album This Is Niecy and the Emotions’ Flowers.

Stepney worked with Ramsey Lewis on two more projects. The first was Ramsey’s followup album to Sun Goddess. Titled Don’t It Feel Good, the album was a funk/rock affair from start to finish. Stepney wrote or co-wrote six of the album’s eight tracks, including the title track and a cover of the EWF hit “That’s the Way of the World.” The title track even features a wordless EWF-style vocal interlude, performed by Morris Stewart and Brenda Mitchell-Stewart. Paul Serrano was on hand as an engineer as he had been for Sun Goddess. Don’t It Feel Good made it to #3 on the Billboard Jazz chart and #5 on the R&B chart. The single “Spiderman” rose to #6 on the Dance Music/Club Play chart.

It’s definitely much more a soul/R&B album with some distinctive slow jams than it is any kind of jazz or fusion album, and in that regard it’s somewhat unique in Ramsey Lewis’ catalog, because no matter what he generally always comes back to that familiar territory that he has commanded like no one else for over fifty years now.

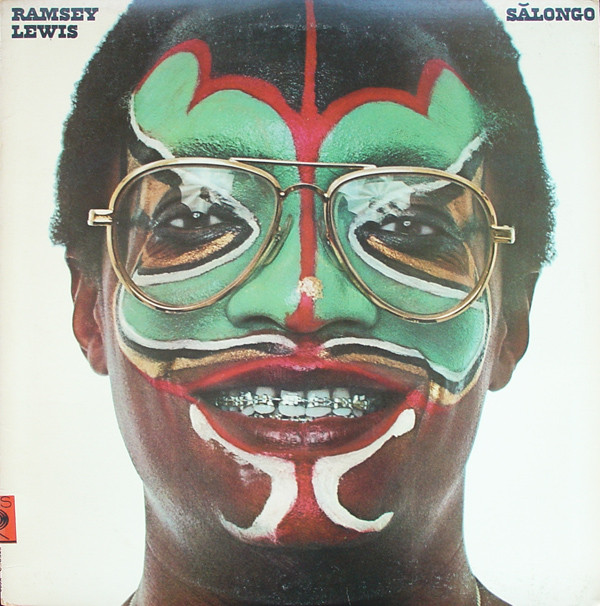

The final Ramsey Lewis album to feature the work of Stepney also brought Maurice White and his old boss together one more time as well. Titled Salongo, it featured more horns and a Latin/World music vibe that was very much in keeping with the direction Maurice White and EWF were headed. Salongo is a great, frequently overlooked mid-70s jazz release and another strong entry in Ramsey Lewis’ catalog.

EWF would go on to become one of the best selling recording and longest running touring acts of popular music. Maurice White passed away in 2016 after a longstanding battle with Parkinson’s Disease. The band continues to perform with original members Ralph Johnson, Verdine White, and Philip Bailey. Ramsey Lewis, now in his eighties, has continued to record and perform as well. Maintaining Chicago as his home base, Lewis has become an elder statesman of jazz. The work that Lewis, White, and EWF did together, particularly on Sun Goddess will always be part of the legacy of their careers and their musical histories.

Beautiful beautiful!!!!!

Thanks, Luis, for reading and commenting. Please come back and check out more articles soon.

-Marshall-