Isaac Hayes and Stax Records were forever linked in terms of their influence on and their promotion of African American culture. As an ace songwriter and session man Hayes was an important part of the label’s rise. When times got tough for both the performer and the label he found the strength to revive both Stax and his own career.

Stax Records, for which Hayes wrote and recorded for many years, had ambitions to become a part of the black community. Co-owner Al Bell was dedicated to a number of African-American causes, including the work of Operation PUSH, led by the charismatic Jesse Jackson, a personal friend of Bell’s.

In 1972, seven years after fierce rioting in L.A.’s Watts ghetto signaled that not all African Americans were happy to just sit back and wait for justice to happen, Bell organized the Wattstax concert. Billed as ‘the black Woodstock,’ the concert drew 112,000 people to hear Albert King, the Staple Singers, Rufus Thomas and Carla Thomas and went off without any kind of major incident.

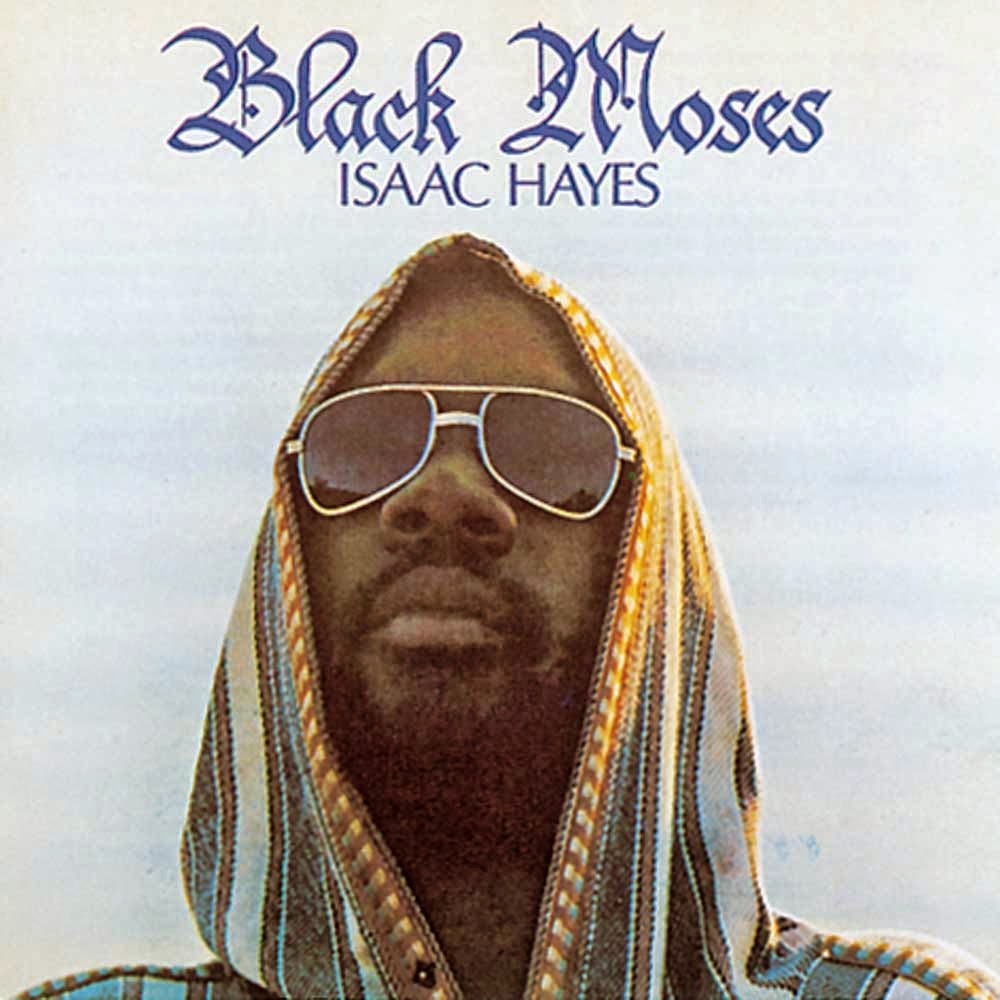

The biggest draw at Wattstax, performing last after being introduced at length by Jesse Jackson, was Isaac Hayes. Hayes had become the record label’s biggest star following the release of his recordings Hot Buttered Soul and Black Moses. With his chain-mail vest, clean-shaven head, and leather pants, he also set a deliberately sexy trend. Hayes rescued Stax and helped it find its way forward in the aftermath of the death of the label’s biggest star, Otis Redding, in 1967.

Stax Records was founded in Memphis in 1957 by white businessman Jim Stewart and his sister, Estelle Axton. Stewart was a banker and part-time fiddle player in country music bands, and he originally intended to record and issue country music on Satellite Records, the label’s original name.

In 1959, Axton convinced her husband to take out a second mortgage on their home and they became equal partners in the label. She and her brother moved the label into the former Capitol Theatre, located in a black Memphis neighborhood. They converted it into a record store and recording studio and began to record primarily black artists. The floor of the theatre was not leveled, in part to save money, which ended up giving the studio space unique acoustics that contributed to Stax’s distinctive Memphis sound.

The pair were forced to change the label’s name because of an L.A. label that already owned the name Satellite. Stax was a combination of Axton and Stewart’s surnames. Axton left her day job to run the record shop, which turned into a hangout for people from the neighborhood as well as black musicians who ended up recording for the record label. “The shop was a workshop for Stax Records,” she once said. “When a record would hit on another label, we would discuss what made it sell.”

It has been noted by more than one performer that Estelle was a large part of the label’s success, encouraging bands and musicians and then talking her brother into signing them. In Axton’s 2004 obituary in the U.K. newspaper The Guardian, Isaac Hayes was quoted as saying: “You didn’t feel any back-off from her, no differentiation that you were black and she was white. Being in a town where that attitude was plentiful, she just made you feel secure. She was like a mother to us all.”

Hayes was already a part of Stax during this period, a songwriter who, with partner David Porter, wrote such hit songs as “Soul Man,” “When Something Is Wrong With My Baby,” and “Hold On I’m Comin’” for soul duo Sam and Dave. In addition, Hayes was part of the Stax production team, along with Porter and Booker T. & the MGs. Hayes’ first session with Stax was playing piano with baritone saxophonist/bandleader Floyd Newman, with whom he landed his first steady job, gigging at the Plantation Inn in Arkansas, across the river from Memphis.

Hayes ended up playing on more Stax sessions than any other musicians with the exception of Booker T & the MGs. His soaring organ work can be heard on “Try a Little Tenderness” as well as countless recordings by Sam & Dave, the Mar-Keys, the Bar-Kays, Rufus & Carla Thomas—virtually the entire Stax roster.

As songwriters, Hayes and Porter were integral to the success of the label. In his autobiography, Rhythm and the Blues: A Life in American Music, Jerry Wexler says: “Porter and Hayes were to the sixties what Lieber and Stoller were to the fifties—poets with precisely the right punch. Their catalog of songs defined the times along with the two great singers they produced for us.”

Wexler says ‘us’ because by this time Stax had entered into a distribution agreement with Atlantic Records, where Wexler had become a partner in 1953. Stax produced the actual recordings in the studio, where Jim Stewart acted as the engineer, using their musicians. The finished tape was sent to Atlantic, with the recording costs borne by Stax and the rest paid for by Atlantic.

As Wexler tells it “We (Atlantic) mastered, pressed, fabricated the package, distributed, marketed, and promoted hard. On every record sold they earned a royalty varying from 12 to 18 percent of retail—with no deductions.” Wexler recognized the unique soul sound that Stax had going for it down in Memphis and he began to send Atlantic artists down to Memphis to record with Stax’ musicians, an arrangement that sometimes rankled Jim Stewart. Stewart came to see the Stax sound and zeitgeist as the label’s biggest advantage and grew less interested in sharing it with artists who were not directly signed to Stax. Nonetheless, the Wexler-Atlantic-Stax arrangement continued to work well until a series of events forced Stax to reassess its future.

Early in1967, Atlantic Records was sold to Warner Brothers, and as a result, a clause in Stax’ distribution deal called for a renegotiation of the contract between Stax and Atlantic. The original masters of all the recordings which Stax had released and had distributed to Atlantic no longer belonged to Stax. Warner refused to renegotiate a deal with Stax, which meant that they no longer owned much of their back catalog and, worst of all, lost rights to the recordings of Sam and Dave.

Stewart sold what was left of Stax to Gulf and Western Company, and Al Bell assumed leadership of the label, with Stewart taking a less active role and his sister selling out her portion of the label. Bell had worked at Stax since 1965 when he signed on as director of promotions. Otis Redding’s death was also a huge hit to the label, depriving it of its biggest remaining star. Bell planned an ambitious round of recording in an attempt to bring the label back as strong as ever.

In 1968, the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. dealt a blow to Hayes, as to the entire world: “I could not create properly,” said Hayes. “I was so bitter and so angry. I thought, What can I do? Well, I can’t do a thing about it so let me become successful and powerful enough where I can have a voice to make a difference. So I went back to work and started writing again.”

By 1969, Hayes had written and recorded the album Hot Buttered Soul, which became an enormous hit for Stax. Along with some of Bell’s other releases, including the newly signed Staple Singers, a new era was ushered in both for Stax and for soul music. Hayes also perfected his ‘Black Moses’ persona, the perfect avatar for the era of black power.

As a star performer Hayes led by example—he was dignified, successful, and led a lifestyle that, while comfortable, stayed clear of some of the excesses seen among many popular recording stars, black and white, of that era.

With Bell, the first African American in an executive position at Stax, at the helm, the label’s artists included Hayes, the Staple Singers, Johnnie Taylor, Rufus Thomas (one of Stax’ first signings in the early Memphis days), the Rance Allen Group, the Bar-Kays, Albert King, a and heady mix of soul, funk, blues, gospel, and rock that was among the best black music being recorded at the time.

By 1976, both Stax and Hayes were in bankruptcy, and Wexler realized what a mistake it had been for Atlantic to sell to Warner. All three recovered, in different ways. The Stax catalog was purchased by Fantasy Records in 1977. Though the original studio was torn down, the Stax Museum of American Soul Music was constructed at the site and opened in 2003. Concord Records purchased Fantasy in 2004 and reactivated the Stax label in 2006.

Hayes went on to release further recordings and eventually find success as the voice of the South Park character Chef. Wexler continued to work in the industry, scoring several notable successes until he retired in the 1990s. The passing of both Hayes and Wexler in August of 2008 ended a notable chapter in the history of African American music and the little record label from Memphis that changed the world with its soul.

Actually, Johnny Taylor, STAX’s Biggest Seller, REFUSED to do WATTS/STAX cause they wouldn’t let Him Close The Show.😎

Yes, Taylor’s brief appearance in the Wattstax film was filmed at his Summit Club performance in September ’72, not at the actual Wattstax festival.

I’ve seen his non-appearance attributed to overbooking but it isn’t difficult to imagine he was miffed at being upstaged by Hayes.

Thanks for reading and taking the time to comment.