by Marshall Bowden

In the acknowledgments of his book Cut ‘N Mix: Culture and Identity in Carribean Music, Dick Hebdige notes that

“In his book There Ain’t No Black In The Union Jack, Paul Gilroy has suggested that music functions within the culture of the black diaspora as an alternative public sphere. Sometimes a reggae toast or soul rap might consist of little more than a list of names or titles. Naming can be in and of itself an act of invocation, conferring power and/or grace upon the namer: the names can carry power in themselves. The titles bestowed on Halile Selassie in a Rastafarian chant or a reggae toast or on James Brown or Aretha Franklin in a soul or MC rap testify to this power. More importantly in this context, the namer pays tribute in the ‘name check’ to the community from winch (s)he has sprung and without which (s)he would be unable to survive.”

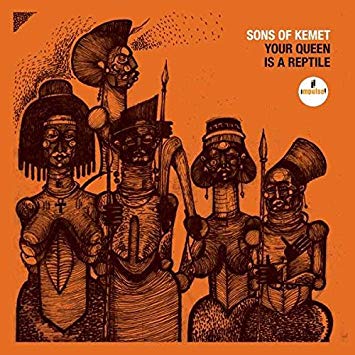

And so it is with Sons of Kemet’s album Your Queen is a Reptile. Each track summons up a powerful, influential, fierce, black woman. From Ada Eastman and Harriet Tubman to Angela Davis and Yaa Asantawa, these women are toasted as queens of the cultures they represent–African, American, Caribbean–and brings them directly into the modern culture of the immigrant diaspora in Great Britain at a time when that country has chosen to isolate itself from the European Union and to reassert the general whiteness of its native culture.

In the album’s final cut, “My Queen Is Doreen Lawrence”, poet/musician Joshua Idehen chants:

Don’t wanna hear that racist claptrap

You chat that chat get clapped back

Don’t wanna take my country back mate

I wanna take my country forward

The album’s title, Your Queen is a Reptile, carries all the diss you might think the name implies: your queen lives in the mud, is ugly, an object not of worship, but of revulsion and ridicule. My queens have a power that comes from their deep wisdom and their actions on behalf of their people, not from some shoddy birthright that can barely be defended with a straight face.

What about the music? People of a certain age will immediately recognize in Sons of Kemet the echoes of dub,ska and 1970s British punk, mingled in with the snaking rhythms of a New Orleans first line, and of the jamming of Albert Ayler. I recall reading once a description of Ayler’s music as sounding like a mariachi band on LSD. Sons of Kemet is a little like that, not in any lysergic influence, but more in the way it channels an amalgam of folk musics and filters it through the musicians’ fiercely personal styles.

The music is energietic, danceable, celebratory, fiery, and like the music of Ayler, Ornette Coleman, and Pharoah Sanders it’s sometimes a bit rough and primitive yet played with conviction and precision that belie its roots in art music.

Shabaka Hutchings, who was born in Britain but grew up in Barbados until the age of 16, doesn’t feel constrained by the trappings of jazz music’s past. While he uses the language of jazz, it’s questionable whether he considers himself a jazz musician, or if he even cares about such labels at this point. Obsessed with rap and hip-hop in his teen years, he now requently practices to rap records.

“When I step on the stage in Sons of Kemet I’m not trying to be Sonny Rollins or John Coltrane, I’m trying to be someone like Capleton or Anthony B or Sizzla, in terms of just the energy that I’m coming up with: That’s who I want to be. My core vocabulary is jazz, but I’m not trying to have the energy of someone in a suit standing stationary in front of a microphone giving a nice round sound, I’m trying to just spit out fire.”

Shabaka Hutchings

It’s worth noting, though, that Hutchings’ playing has much of the fire of Coltrane and all of the rhythmic intensity and playfulness of Rollins. He’s joined by tubist Theon Cross, whose background is also Caribbean, and two drummers. Of course the music is primarily rhythmic, with the tuba providing a bass line, and Hutchings coming in on top of that.

Your Queen Is a Reptile is a must hear album for those who love the energy of ska, dub, reggae, soca, Caribbean music, avant garde jazz, New Orleans marching bands, whatever. It’s hard to think of an adventurous music fan who wouldn’t enjoy this record.