You’re Iggy Pop and you’ve just released an album that captures the imagination of fans and critics alike, forging a new direction that takes you away from the dead-end you were supposedly stuck in, and the future looks pretty bright. What do you do now?

Correct answer: you take some time to evaluate the situation and embark on writing and recording a record that does absolutely nothing to capitalize on this momentum. Instead, you meander off in a new direction that may or may not prove to be successful or popular.

You’ve done this many times in the course of your career. When you arrive at the doorstep of your solo career following the self-destruction of your seminal band The Stooges, you go to Berlin with David Bowie who helps you to record two of the strongest albums you will ever release. So, of course, you next sign on to Arista Records and proceed to record a strong album that puts you into the mainstream of what’s happening right now: punk rock. You follow that up with a less focused but still substantial album, and then you veer into the ditch and record am an album that alienates your newfound following by trying too hard for a hit record.

Get more articles like this. Sign up for NDIM’s newsletter, sent to your email box every Tuesday. What’s coming and where to hear it.

Next you head to Haiti with your girlfriend and then record a really left-field record on your friend’s label, a record that no one likes and that goes out of print for some time (though of course it is later reissued as a ‘forgotten classic’). It takes you four years to more resurface, again under Bowie’s direction, with a definitive ’80s album that garners you a hit single and more attention than you’ve had in years.

Now you decide to go back to your heavy rock roots and you hire a garage band and write garage music. Just like the Stooges all over again. Except not. You decide to usher in the ’90s with an album that runs the gamut of what you do, trying to display all (or at least many) of your various moods. It doesn’t do badly at all (another hit single), but you decide to spend the rest of the decade retreading the same garage territory that made your bones in the first place. But it’s drudgey, and people are talking about how you’re stuck in a rut.

You continue to do this into the 2000s except for a brief interlude as a poet (1999’s Avenue B). You disappear from view for a while before resurfacing with an album of strong songs, thoughtfully arranged. Again there is some praise from those who had long ago written you off. You follow that up with an album of the crooning thing. And then, four years later you resurface with a new collaborator (Josh Homme) and produce a record of stunning new material that takes you into a different sonic universe than you’ve been inhabiting. The album is wildly successful and so is the ensuing tour, which is preserved on record.

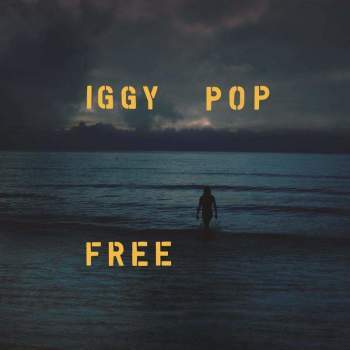

It’s a couple of years later. What do you do now? Well, you hire new musical collaborators and head in a completely different direction, of course. So now we have the new Iggy Pop album, Free, pretty much unannounced, and it is definitely different from Post Pop Depression but in a good way. Which is to say, this time Iggy makes a move opposite to what you’d expect from most artists, and it works wonderfully for him.

One thing that lends a completely new sound to the album is the presence of avant-garde guitarist Noveller (AKA Sarah Lipstate). Lipstate is a filmmaker who turned her effects-laden guitar work into a successful side project and has since toured with St. Vincent, Mary Timony, Wire, and now Iggy Pop. Her gorgeous, ambient, layered guitar work is sometimes reminiscent of Robert Fripp’s ‘Frippertronics‘ as well as the work of collaborator Brian Eno, and she freely discusses them as influences. Her most recent solo album, 2017’s A Pink Sunset For No One plays strongly with their influence, but its there on the earlier album as well. Yet Lipstate also sounds like the love child of music as diverse as Sonic Youth and Steve Tibbetts.

On Free she creates soundscapes that emerge and recede behind Iggy’s vocals and poetry and there’s a sense of both uncertainty and the relief of arriving home. On the more rock-oriented tracks she doesn’t try to provide a base for the song, allowing that to fall to the drums. Instead she’s interacting and commenting on the vocals in a way that is as supportive of Iggy as any musician he’s worked with.

Iggy’s other newfound collaborator is Leron Thomas, a trumpet player, composer, arranger, and producer who plays everything from straight-ahead jazz to hip hop. His work on Free is mostly open and subdued, providing an introspective, meditative aspect as he rides high on Lipstate’s clouds of sound, though he waxes suitably bluesy and more frenetic on the ’60s swinger “James Bond.”

Free is described by some reviewers as uneven, but honestly, it seems like one of Iggy Pop’s most consistent efforts in a long time, and one I can envision listening to repeatedly for the foreseeable future. If there’s a skippable track it’s “Dirty Sanchez” which many have derided as juvenile and unbecoming of the sophisticated atmosphere Iggy seems to be pursuing on Free. Which I’ll agree to, but it’s not horrible and this is Iggy, after all.

But “Loves Missing” and “Sonali” are absolutely stunning tracks that follow the introductory soundscape “Free.” The former isn’t dissimilar to some of the songs on Pure Pop Depression, and “Sonali” is an easygoing, jazzy track that finds Iggy intoning lyrics that combine worldly wisdom with platitudes (‘Stay in your lane’). In short, these are really good Iggy Pop songs.

The second side (and yes, Free is available on vinyl) is comprised of tracks that are more poetic, with Iggy reading or declaiming lyrics in much the way he did on Avenue B. But one never gets the impression that Iggy is being lazy (as on Zombie Birdhouse) or not committed to this work. Although there is a voice on these tracks, the overall effect is reminiscent of David Bowie’s instrumental Side Two of Low and Heroes. It makes you think “is this an Iggy Pop album I’m listening to?”

Iggy Pop himself has described Free as ‘an album where other artists speak for me,’ and perhaps that’s true, as he performs poetry written by other people. First is “We Are the People,” by Lou Reed, a poem Iggy saw in a collection of Reed’s poetry which was written in 1970 but fits with today’s situation as though written yesterday. That’s followed up by Dylan Thomas’ “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” with its invective against acceptance of the inevitable.

He concludes with his own “Dawn,” a kind of looking back that seems inevitable in the wake of the deaths of The Stooges’ Ron and Scott Ashton and his close friend and mentor David Bowie. “At my stage of the game, you don’t void out memories” he says, and who are any of us to disagree?