The trumpet player who had become known as ‘the new Miles’ was at a low point in the mid-70s until the V.S.O.P. quintet revitalized his playing.

The death of Freddie Hubbard eleven years ago was the final note of a career that, for many listeners, had ended years before. True, Hubbard had made some attempts at a comeback in his later years and recorded several good records. But ultimately, his best work is that he did for the Blue Note label as both a leader and as a member of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers in the 1960s. His tenure at Creed Taylor’s CTI label produced albums that managed to be contemporary jazz fusion while maintaining some elements of a hard bop edge that gave these records a well-deserved reputation as contemporary jazz classics.

Hubbard spent the rest of the ‘70s becoming a progressively more pop-oriented artist, and the recordings he made for the Columbia label to end the decade were universally reviled and most have never been in print on CD (though they are largely now streamable).

His work with the group VSOP, starting with The Quintet in 1977, gave listeners a chance to hear Hubbard playing straight-ahead modern jazz and to realize that his chops were still there. VSOP was essentially the second great Miles Davis Quintet (Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Tony Williams, and Wayne Shorter) without Miles. Instead, there was Freddie Hubbard, whose fiery hard bop trumpet and flugelhorn work allowed him to be much more than a mere stand-in for Miles.

Very possibly as a result of his work with VSOP Hubbard started to move out of the slum of pseudo-jazz instrumental pop where Columbia had relocated him and back into the land of mainstream jazz. The 80s saw him playing mainstream jazz with his usual fire once again.

In 1992 his lip was injured and there was a time when it was doubted that he would play again at all. Slowly, he rehabilitated his facial muscles until he was able to play again. Of course, it is difficult to objectively evaluate someone’s playing when one knows they are working against some nearly insurmountable obstacle in order to play at all, but it is generally agreed that his playing never truly recovered its former glory. The point, though, is that Hubbard did what he had to in order to survive the late 1970s when the market for any kind of mainstream jazz was absolutely zero, and when conditions improved, he began to work back toward playing the kind of music that he wanted to play.

So much of Hubbard’s life paralleled or followed that of Miles Davis. Hubbard was ‘the new Miles’ almost from the time people became aware of him. The original liner notes of his 1961 Blue Note album Hub Cap recount how Miles told Leonard Feather that Hubbard was one of the young jazz musicians that had impressed him. When Miles moved into the second great quintet, Hubbard moved into Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

When Miles went electric, Hubbard did as well, moving to the CTI label to create his own fusion work. When Miles vacated the stage in the mid-70s Hubbard played with VSOP and began his own musical rehabilitation, just as Miles did for his own early ‘80s comeback. And like Miles, Hubbard was beginning to make good music again in the final phase of his career. One wishes that both men could have hung around a while longer for one more big recorded statement.

As for the music on Hub Cap, it is straightforward post-bop mainstream jazz with a deep three-horn front line (Hubbard, Julian Priester, and Jimmy Heath) and a heated rhythm section consisting of Cedar Walton, Larry Ridley, and Philly Joe Jones. Of the six original tracks, four are composed by Hubbard, with one by Walton and one by Randy Weston. This excellent outing is Hubbard’s third for Blue Note, and he had already succeeded in causing significant buzz among established musicians.

Lest one imagine that Hubbard was a very talented derivative of Miles Davis who never quite changed the jazz landscape the way Miles did and therefore is remembered merely as a decent player, keep in mind that Freddie was much in demand as a sideman and it was in these venues that he did some of his most outside and modern work.

Appearances on Eric Dolphy’s Out to Lunch and Outward Bound, on Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz, on Coltrane’s Ascension, and on Oliver Nelson’s Blues and the Abstract Truth put Hubbard square in the middle of the modern jazz highway. But Hubbard never quite fit all the way into that crowd just as he couldn’t quite confine himself to playing swinging post-bop jazz exclusively.

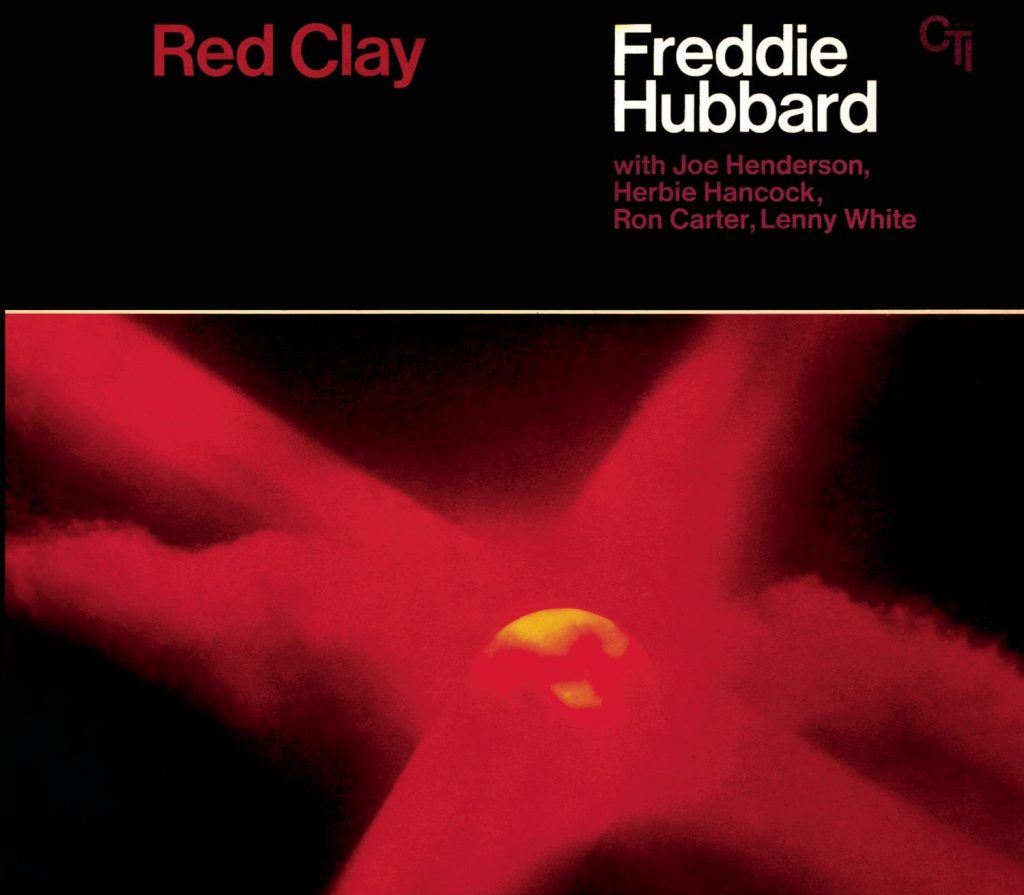

In 1970, Hubbard signed with CTI Records and proceeded to record the album that many still consider his best: Red Clay. This is pretty straight-ahead jazz with a sometimes rock rhythm section feel. Its main claim to being ‘plugged in’ is that Herbie Hancock plays the Fender Rhodes electric piano. The title track, with a lilting boogaloo rhythm, gives rise to powerful solos by Joe Henderson on tenor sax and Hubbard himself. Ron Carter is on bass, and Lenny White, who would soon join Chick Corea’s Return to Forever, on drums. Hancock’s work here gives testimony to the fact that he was one of the prime inventors of the jazz language for electric keyboards.

This was so much less extreme than what Miles was doing, particularly live, that it’s hard to imagine, with hindsight, that this would be considered anything other than jazz. OK, so John Lennon’s ‘Cold Turkey’ is a slightly strange tune selection, but it provides a basic groove for some fiery jamming. The reissued version of the album also features an eighteen-minute live version of ‘Red Clay’ that features a CTI All-Star lineup that includes George Benson, Stanley Turrentine, Johnny Hammond, Ron Carter, Billy Cobham, and Airto. It’s a bit more groove-driven and less relaxed than the studio version, and the performances are all good.

Hubbard recorded several other albums for CTI, including Straight Life and Sky Dive. Some listeners feel that these releases lack the drive of Red Clay and presage Hubbard’s drift into pop instrumental music. While it’s true that these releases are pretty laid back, and that more elements (larger backing groups and arrangements by Don Sebesky) are added, I do not agree that these are lesser releases. Sky Dive, in particular, has some exceptional playing, and the arrangements, apart from an occasional misstep, come across like a new Birth of the Cool.

Unfortunately, Hubbard’s tenure at Columbia Records did descend into pure pop pap, though to be fair, it was a difficult time for jazz musicians to survive, to find an audience or opportunity for recording, and Hubbard did what he had to in order to keep his career going.

But in the midst of this period, an amazing thing happened. The Miles Davis Quintet was reunited—without Miles who, as usual, refused to look back to what he had already done. Freddie was the natural replacement, and he played wonderfully, strong and lyrical, on the VSOP performances he was part of.

The group’s first studio recording and live recording set a high standard, though there was some reluctance on the part of many jazz listeners to accept this group playing this music. All of the members, like Miles, were doing something very different now. Tony Williams had helped invent jazz-rock with his group Lifetime. Ron Carter was more or less the house bassist at CTI. Wayne Shorter was playing with Weather Report, while Herbie Hancock had recorded the jazz-funk classic Headhunters and continued to record a funk/soul hybrid with regular forays into the straight-ahead and the acoustic piano.

The difference was most striking, perhaps, when looking at Freddie Hubbard. Here he was, in the midst of his schlockiest, least musically rewarding period, and he was suddenly able to pop into this group and perform with the energy and punch that he hadn’t demonstrated since his Blue Note days.

In 1979 the group recorded two live performances in Japan on the album Live Under the Sky, only released in Japan until its US release in 2007. This is a high-energy band that plays straight forward modern post-bop jazz with absolutely no gimmicks, no electronics, and nary a pop song in sight. The Japanese audience responds with the verve generally reserved for rock stars. It’s great to hear Freddie Hubbard in concert with this stunning group of musicians and realize that he could still play like this, probably would have continued to play like this forever, if anyone back home was the least bit interested in listening.

Freddie was never looked at as the “new Miles”, he was always looked at as his own man.

First off, Freddie was a way more firey and aggressive trumpeter than Miles and played with a far superior technical command of the horn. This is not a put down towards Miles as I still consider him the better and more visionary artist overall.

But in terms of playing earth scorching red hot trumpet, nobody did it like Freddie Hubbard.

And yes, even his most commercial recordings of his fusion period feature him playing with his signature jaw dropping fire and flare. Contrary to what you wrote he still played with all his energy and punch during that period.

Also, on some of those mid 70’s fusion albums Freddie would still include some fierce straight ahead swinging numbers (check out “Spirits of Trane” from the album Keep Your Soul Together and uh, hold on for dear life). He didn’t wait til VSOP to return to playing straight ahead.

And let me tell you, as a jazz trumpeter myself I can attest that Freddie has been one of the premier influences on the last several generations of trumpeters of the last 50 plus years.