New Directions in Music Song Remains the Same Series

by Marshall Bowden

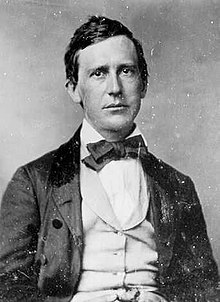

Stephen Foster occupies an uncomfortable space in the history of American music. On the one hand, Foster was a musical pioneer who made a living from writing songs before there existed any real music industry and who was a pop star in terms of the familiarity of his music to, and its reach among audiences of the time. On the other hand, Foster’s songs often glorify life in the antebellum American South and many of them were written for that peculiar American institution, the minstrel show. As recent events in Virginia demonstrate, blackface is a ‘tradition’ that has been particularly slow to die off.

There are indications that Foster’s attitudes towards slavery and towards slaves themselves changed in the period immediately preceding and during the Civil War as well as some documentation to support the idea that he sought to create songs that addressed African Americans as human beings and to try and arouse some empathy for their plight on the part of listeners. But it’s difficult to listen or read the lyrics to the complete “O Susanna” or “Away Down South” without thinking that the man who wrote them was an apologist for something that continues to be a blemish on American history.

Foster spent the earliest part of his career writing songs specifically for minstrel shows. He sold his song “Old Folks at Home” to E.P. Christy, leader of the Christy Minstrels, one of the most popular and well known minstrel groups. Christy paid Foster not only for the exclusive rights to use the song, but also to be officially credited as the song’s writer.

Minstrelsy was big business, not only for the successful producers and performers in the biggest shows but also for the music business. People wanted to sing and play the songs they knew from the shows at home, and so publishers such as Firth and Pond, with whom Foster had a contract, employed some 20 men to produce and print sheet music for 200 songs yearly from these shows. In the words of writer Eric Lott in his book Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, “In this form blackface minstrelsy entered the middle-class parlor.” (Lott, page 174)

And so did Stephen Foster. Besides the “Ethiopian” songs which he wrote for the minstrel shows in a dialect that was meant to mimic that of black American slaves, Foster was also able to write the more genteel songs that were performed in the parlors of average Americans’ homes. Blessed with the ability to write a memorable melody and a sentimental lyric, Foster scored big with songs like “My Old Kentucky Home” and “Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair.”

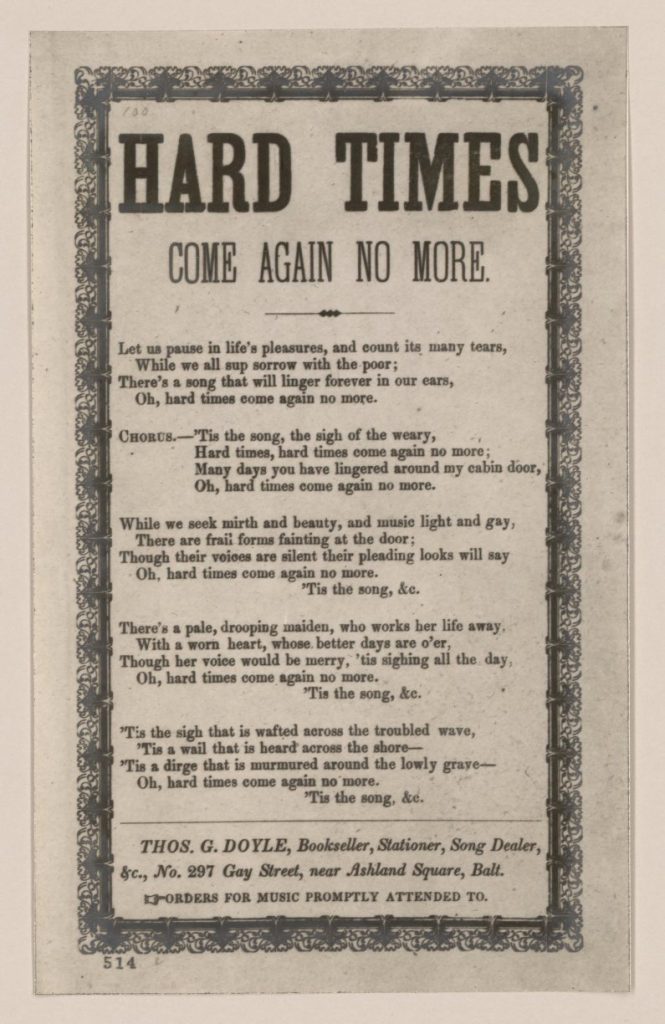

In 1855 Foster penned a song that was unique among his collected work. The song was “Hard Times Come Again No More”, possibly named after the recently published Charles Dickens novel Hard Times. In the song, Foster laments difficult economic times, and the song has a hymn-like quality that suggests not only economic hardships but the physical and spiritual hardships that come with it. In its original arrangement it had the four part chorus typical of minstrel numbers but it has no dialect and no minstrel themes.

It’s a lament and a rallying cry at once, unique among Foster’s oeuvre, and Foster penned its lyrics during a season of loss: a two year period during which his best friend and both of his parents passed away, he separated briefly from his wife, and his career was beginning to sag. His songwriting output diminished and he was forced to draw income against future royalties from his music publishers, eventually selling all rights to his songs outright to settle his debts.

But “Hard Times Come Again No More” is like a singular cry of protest from the depths of Foster’s soul. The first verse sets the scene:

Let us pause in life’s pleasures and count its many tears

While we all sup sorrow with the poor:

There’s a song that will linger forever in our ears;

Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

Followed immediately by the rending chorus:

Tis the song the sigh of the weary; Hard Times, Hard Times, come again no more; Many days you have lingered around my cabin door, Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

It’s a song about poverty–financial poverty first and foremost, but it also hints at a poverty of spirit, of general misery. What’s refreshing about it, what makes it stick in our craw, is its honesty. It doesn’t flinch or pull back from showing real human suffering, bringing it to the very entrance to the drawing room: “Let us pause in life’s pleasures.”

It raises the question of who the intended audience for this song was. It’s not a minstrel song or a plantation song. There is no dialect and the singer is not identified as being black. It cuts across racial lines and that has long been identified as the most dangerous realization that people in a democratic society can come to: the realization that divisions along racial and ethnic lines are intended to keep people from realizing and voting their true interests.

In 1967-68 Martin Luther King Jr. began to organize the ‘Poor People’s Campaign’ which sought to cut across racial lines to unite people of all kinds in holding their government and society to the promise of doing better for those who were economically disadvantaged. From the ghettos of Chicago to the coal mines of Appalachia, King saw the misery of those who had nothing and he knew they had a common source: indifference and greed.

In his famous speech the night before his assassination, King reminded people of this need for unity:

“You know, whenever Pharaoh wanted to prolong the period of slavery in Egypt, he had a favorite, favorite formula for doing it. What was that? He kept the slaves fighting among themselves. But whenever the slaves get together, something happens in Pharaoh’s court, and he cannot hold the slaves in slavery. When the slaves get together, that’s the beginning of getting out of slavery.”

So in throwing down with the poor and the downtrodden of any race or ethnicity, Foster was on the money with “Hard Times Come Again No More.” But that didn’t make the song a success or halt the general slide of Foster’s songwriting and publishing career.

Yet, the song proved weirdly prescient. First, it presaged much of the suffering of the Civil War, so much so that it is sometimes misidentified as a Civil War song. Second, it was in many ways the soundtrack of Foster’s later life in New York City where, despite working industriously on new songs he ended up in a cheap boarding house where he died as a result of injuries from a slip and fall in his room.

“Hard TImes Come Again No More” rode quietly into the sunset along with Foster himself. In the end, the composer was remembered for a handful of songs, some tainted by their minstrel show origins, and others hopelessly sentimental.

But that’s not how the story of “Hard Times Come Again No More’ ended.