Spanky & Our Gang, John V. Lindsay and the counterculture meet in the whirlwind of 1968

by Marshall Bowden

1968, the summer of the New York Urban Coalition’s ‘Give a Damn’ campaign was much different than that of 1967. The summer of love rose in a giant puffy cloud over the San Franciso Bay area and wafted out across the country. But now that cloud was turning darker.

For Spanky and Our Gang, a Chicago-based pop music group whose music helped spawn the sun-drenched subgenre ‘sunshine pop,’ as for many Americans, it turned into the year.

Spanky and Our Gang blew in on the breeze of the much-hyped Summer of Love with the melancholy but gorgeous “Sunday Will Never Be the Same.” A year later they were spokespeople for Mayor John Lindsay’s ‘Give a Damn’ campaign as well as the scourge of America according to Richard Nixon.

_____________________________________________________________________

Elaine McFarlane was a bluesy jazz/pop singer in Chicago who was influenced by the rise of the folk music scene to join a group called The New Wine Singers in 1963. New Wine mixed folksy pop sounds with protest and a helping of old-time trad jazz. She met group musician Malcolm Hale and acquired her nickname, “Spanky” in part because of the similarity of her surname to that of child actor George “Spanky” McFarland.

By 1965 McFarlane had moved on and she and Hale were interested in starting a group. The club owner at Mother Blues where McFarlane was working as a waitress told her to put a house group together that could open for the outside acts the club booked. Oz Bach and Nigel Pickering, two musicians McFarlane had met in Florida, relocated to Chicago and joined the group. Initially they called themselves Spanky and Our Gang as a joke, but the group began to be written about in local newspapers and the name was out there, so they decided to go forward with it.

The group’s sound was centered around three part harmony in the manner of several successful folk groups–Peter, Paul & Mary, The Kingston Trio–and like that latter group they also performed some comedy routines to round out their musical set in order to meet time requirements for the clubs where they worked.

“We sang some show tunes, a little Andrews Sisters, a little rock ‘n’ roll. We were pretty eclectic, kind of a jug band that sang,” McFarlane told a reporter in 2007. Pretty soon the group was ready to move out of Mother Blues and play larger clubs. In 1966 Mercury Records, headquartered in Chicago, heard about them and offered them a record contract. The Mamas & the Papas had released their first album, combining vocal harmonies and a folk rock/pop sound and Mercury was looking for a similar act.

The band recorded “Sunday Will Never Be the Same” after spending the better part of a year with producer Jerry Ross, who helped polish their sound. The song had been written by songwriters Terry Cashman and Gene Pistilli and recorded by them as a vocal trio along with Tommy West. The song was offered to The Mamas & The Papas and rock group The Left Banke, both of whom turned it down. Ross felt it would make an excellent song for Spanky and Our Gang.

The single was a hit, prompting the release of two more singles and the hiring of drummer John Seiter. Mercury needed an album, and they put together a self-titled release featuring the three charting singles and some other tracks that were of varying quality, which the group wasn’t entirely happy with. Their bluesy, boozy “Brother Can You Spare a Dime?” was still being worked out, while “Ya Got Trouble In River City” from The Music Man, is hopelessly corny hokum.

Spanky & Our Gang Select Discography

There’s some left field stuff, though, that makes you realize that there’s more here than meets the eye. A pair of songs from Michael P. Smith, “(It Ain’t Necessarily) Byrd Avenue” and “Commercial” are informed by the rising drug culture. “5 Definitions of Love” by Bob Dorough pointed the way the group would head in their second album. In fact, the group hired Dorough and his production partner Stuart Scharf to work on their second album, Like to Get to Know You. At the same time, Oz Bach left the band and was replaced by Kenny Hodges along with additional guitarist/vocalist Lefty Baker.

Baker brought another voice to the band and they rearranged their sound around intricate six-part vocals. Meanwhile, as with so many 1960s groups, Dorough and Scharf brought in a variety of session musicians to play the arrangements they wrote while the band members concentrated on the layers of vocals. Dorough and Sharf had worked, both as musicians and producers, with many top jazz musicians. Studio players that worked on the Like to Get to Know You included Max Bennett, Larry Knechtel, Mike Deasy, and Hal Blaine.

Scharf’s title track has a jazzy, loungey sound and feels reminiscent of Burt Bacharach’s arrangements at the time. It’s a really unique single that has a theatrical element as well (on the original album version), with the vocalists apparently at a cocktail party enacting a pickup attempt before slipping into the song itself.

Spanky and Our Gang were bona fide stars when Like to Get to Know You was released in April 1968.

_____________________________________________________________________

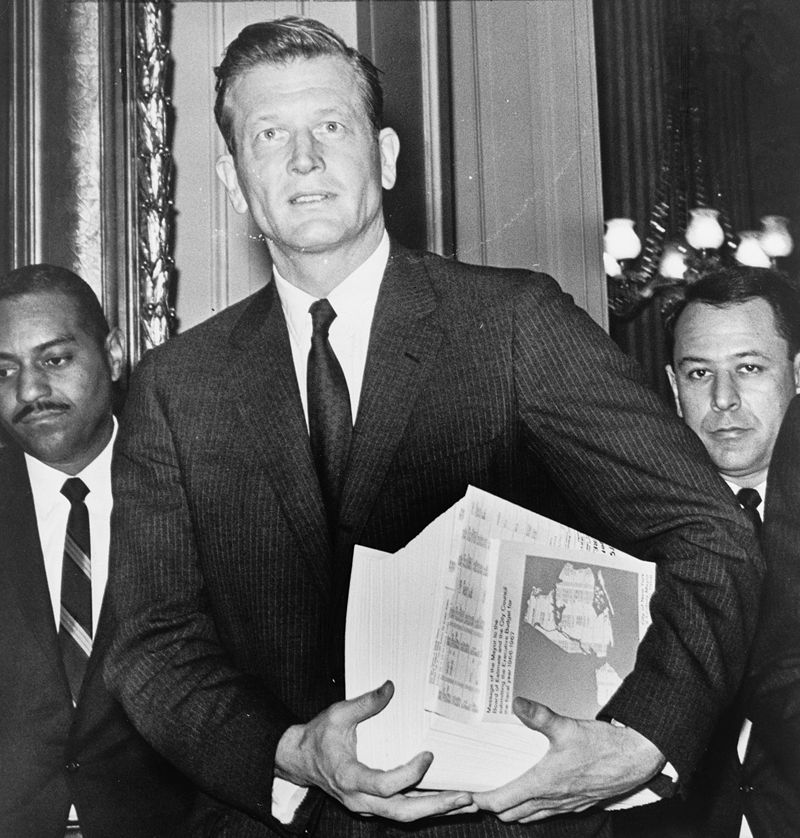

John Vliet Lindsay first got himself elected Mayor of New York City in 1965. Lindsay was that rarest of unicorns: a socially liberal Republican. As a Representative for New York’s 17th “silk stocking” district, Lindsay supported the establishment of HUD and a National Foundation for the Arts and Humanities as well as increased federal support for education and Medicare.

By Orlando Fernandez, World Telegram staff photographer – Library of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c33401, Public Domain, Link

This put Lindsay at odds with a Republican party that was becoming increasingly conservative, but it was generally well accepted by his congressional constituents in the wealthiest district in the United States. Lindsay himself came from an upper-class background; his father was an investment banker and he was educated at private boarding schools and at Yale. Yet having worked briefly with the Eisenhower administration he was part of a relatively liberal Republican tradition that was seeing its twilight as the 1950s drew to a close.

And so Lindsay earned the term maverick. He refused to vote in favor of bills that would allow the opening of mail coming from Communist countries or increase the Post Master General’s ability to seize obscene material. By 1964 he found his party sufficiently transformed that he refused to support the Republican nominee for President, Barry Goldwater. He was elected as a Republican with assistance from the Liberal Party of New York in a three-way race; William F. Buckley ran as a Conservative to counter Lindsay’s ‘soft’ Republican stance. Lindsay defeated him as well as the Democratic candidate, city Comptroller Abraham Beame.

Lindsay was elected mayor largely by liberal middle-class voters who, while privileged, were concerned about the plight of those less fortunate. They could relate to John Lindsay both in terms of his background and political views on social issues.

Make no mistake: Lindsay was a shrewd political operative and was good at playing the political game. In his obituary for The Guardian, journalist Godfrey Hodgson wrote:

“Six foot four, with blond hair and greenish eyes, Lindsay was often compared to John F Kennedy, and the same adjectives were applied to him as to Kennedy, four years his senior: patrician, elegant, cool, glamorous, stylish. He was fascinating to the media and adept at manipulating them. From an early stage in his career he thought in terms of an eventual run for the presidency.”

Lindsay was, in fact often compared to JFK, obsessed as the public was with finding the next iteration of the martyred leader. In an Esquire article written while Lindsay was running for his first term as NYC mayor, Noel E. Parmentel proclaims Lindsay “more honest, more honorable” than Kennedy. Yet compared to Kennedy, he is “the dull, honest plodder.”

Hodgson also relates the story of the message that was left on Lindsay’s desk in Gracie Mansion, the mayor’s residence. Lindsay’s Democratic opponents left a shamrock on the desk as a reminder of Transit Worker’s Union leader Mike Quill. The Irish labor leader brought the city to a halt with a transit strike on Lindsay’s very first day in office. The strike lasted twelve days, and Quill extracted $60 million in wage increases and benefits from the city. The settlement forced Lindsay to introduce new taxes to meet its costs. Quill suffered a fatal heart attack on January 28th, 1966, three days after the strike was settled.

The transit strike was not the last labor dispute for Lindsay, nor did New York City become easier to manage. As the 1960s wore on, the city became divided, like America, along racial and ethnic, socioeconomic, and religious lines. Lindsay became unpopular with the city’s working class Irish and Italian populations, pursuing policies that were designed to help level the playing field for black and Puerto Rican communities while at the same time reducing corruption among law enforcement and labor unions.

President Johnson appointed Lindsay to the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, which became known as the Kerner Commission. The commission was to look into the causes of race riots in American cities. Their report, released one month before riots devastated many cities in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, determined that the country was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white–separate and unequal.”

On the night of King’s assasination, Lindsay traveled to Harlem and walked the streets there, expressing grief for the death of Dr. King and talking about his ongoing work against poverty in the city. David Garth, a political consultant for Lindsay, was there that night and remembers it this way:

”There was a wall of people coming across 125th Street, going from west to east…I thought we were dead. John raised his hands, said he was sorry. It was very quiet. My feeling was, his appearance there was very reassuring to people because it wasn’t the first time they had seen him. He had gone there on a regular basis. That gave him credibility when it hit the fan.”

As 1968 slogged on an attempt to decentralize the New York public school system proved disastrous when it led to a citywide teachers’ strike. There was a nine day sanitation worker strike that led to piles of garbage in the city streets. And Lindsay’s Republican Party was marching ever farther to the right, putting him in a difficult position.

“The last six months of 1968 were ‘the worst of my public life,’ Mr. Lindsay later said. The schools were shut down, the police were engaged in a slowdown, firefighters were threatening job actions, sanitation workers had struck for two weeks and the city was awash in garbage, and racial and religious tensions were breaking to the surface.”

John V. Lindsay, Mayor and Maverick, Dies at 79 by Robert D. McFadden, New York Times, December 21, 2ooo

_____________________________________________________________________

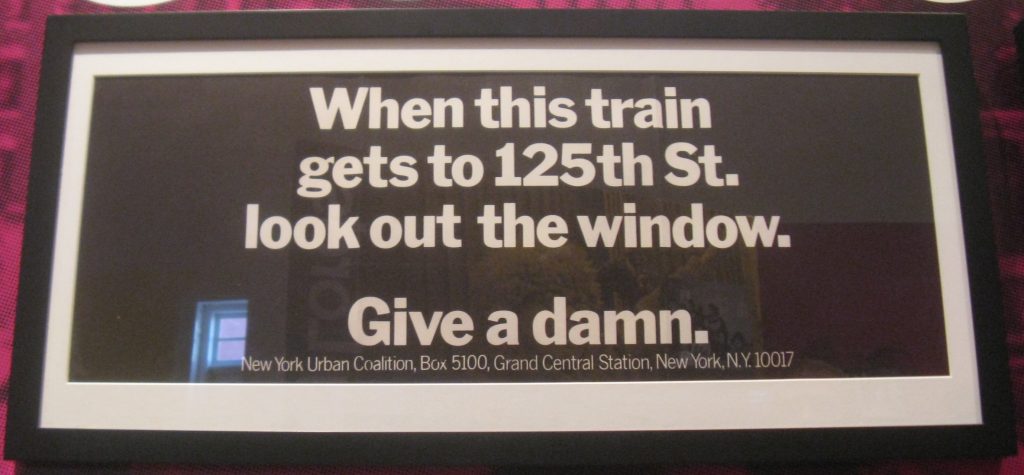

In 1967 Lindsay created the New York Urban Coalition to support the needs of urban ghetto residents by assisting with children’s education, adult job training, aid to minority businesses, and help dealing with unscrupulous landlords and rent gouging. The coalition consisted of partners from major law firms, business leaders, and activists. The NYUC spent $10 million between 1968 and 1969, all of which was privately raised. (The Ungovernable City by Vincent Cannato, 2001 Basic Books, pp. 215).

To properly promote the coalition to New Yorkers a campaign was created by the advertising firm of Young & Rubicam. They came up with a slogan designed to prod liberal middle class voters–the very voters who had put Lindsay in Gracie Mansion to begin with. That slogan, “Give a Damn” echoed the sentiments expressed by Lindsay in a Readers Digest interview in August of 1968, titled “We Can Lick the Problems of the Ghetto If We Care.”

Photograph by John Albok Museum of the City of New York, Prints & Photographs Collection

The Give a Damn campaign hit all the stops in an effort to make the campaign viral in 1968 terms. There were newspaper articles and press releases, buttons and a song. According to a clip in the July 13, 1968 edition of Billboard magazine, the song “Give a Damn” was written by Bob Dorough and Stu Scharf specifically for Mayor Lindsay’s campaign, and it was recorded by Spanky and Our Gang and released ‘as a public service’ by Mercury.

The song starts with an invitation to look at what privileged people often ignore:

If you’d take the train with me

Uptown, thru the misery

Of ghetto streets in morning light

It’s always night

Take a window seat, put down your Times

You can read between the lines

Just meet the faces that you meet

Beyond the window’s pane

The next verse is more graphic in its depiction of ghetto life–it seems designed to shock

Or put your girl to sleep sometime

With rats instead of nursery rhymes

With hunger and your other children

By her side

And wonder if you’ll share your bed

With something else which must be fed

For fear may lie beside you

Or it may sleep down the hall

The final verse suggests that the days of rioting in the streets are far from over, as Linsday himself said following the Johnson administration’s decision to shelve the Kerner report without enacting its suggestions for increasing racial equity:

Come and see how well despair

Is seasoned by the stifling air

See your ghetto in the good old

Sizzling summertime

Suppose the streets were all on fire

The flames like tempers leaping higher

Suppose you’d lived there all your life

D’you think that you would mind?

The chorus ties these scenes together with a public service mantra

And it might begin to teach you

How to give a damn about your fellow man

The music itself is not overly heavy, a timely arrangement using horns, and the group’s harmony is in fine form. It’s fair to say that under Dorough and Scharf’s direction, Spanky and Our Gang were releasing records every bit as catchy and sonically rich as the Mamas and the Papas. Both groups had come to be identified as “sunshine pop” but it’s difficult to imagine John Phillips and crew recording a song remotely like “Give a Damn.”

The song would probably have been a #1 hit for Spanky and Our Gang except for one thing: some radio stations refused to play the song because of the use of the word “Damn” in the title. Language was often used as a way to censor songs from radio and television performance when the real issue was the message the song conveyed.

The conservative-trending Republican party, with Richard Nixon moving solidly into place as its leader, did not want songs about children sleeping with rats to be broadcast. He promoted himself as the ‘law and order’ candidate who sought to restore standards of decency and normalcy that were trounced by foul-mouthed street protesters. Dubbing his constituency ‘the silent majority’ Nixon set a tone that brought the full weight of the U.S. government to bear on denouncing the counterculture and its representatives.

But despite the best efforts of censors, “Give a Damn” become a regional hit and reached #43 on the Billboard Singles chart. Spanky and Our Gang were booked to perform the song on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.

The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour was a highly successful show for CBS, but by 1968 it had become a problem child. Tom and Dick Smothers provided a variety program that was similar to the Ed Sullivan Show in that it provided a chance for both new, upcoming talent to be seen right alongside veteran performers, ensuring an audience of both young and older viewers. In addition, the brothers performed as a folk music duo and did comedy bits, a formula that Spanky and Our Gang had also used in their early days. The problem was that many of their guests–Jefferson Airplane, The Who, George Carlin–and even regulars like Pat Paulsen and the Smothers Brothers themselves, were members of the counterculture or sympathized with its anti-war, anti-establishment message.

According to David Bianculli, author of Dangerously Funny: The Uncensored Story of the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour:

“First, individual words and phrases that CBS found objectionable were cut from skits after rehearsals or edited out of the final master tape. Then entire segments were cut because of their political, social, or anti-establishment messages…For every battle the Smothers Brothers won, CBS sought and got revenge. When The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour wanted to open its third season by having Harry Belafonte singing “Don’t Stop the Carnival” against a backdrop reel of violent outbursts filmed in and around that summer’s Democratic National Convention, CBS not only cut the number completely, but added insult to injury by replacing it with a five-minute campaign ad from Republican presidential nominee Richard M. Nixon.”

Spanky and Our Gang’s appearance on the program sparked some complaints in the form of callers to CBS objecting to the use of ‘obscenity’ on the air. It has long been reported that one of those callers was Richard Nixon himself.

_____________________________________________________________________

In October of 1968, founding band member Malcolm Hale was found dead in his apartment in Chicago. His death was reported as due to bronchial pneumonia at the time, but a 2007 book claimed that he actually died from carbon monoxide poisoning from a faulty heating system. Hale’s death had a profound influence on the group, one that caused them to reconsider whether they wanted to continue as Spanky and Our Gang, and in the end, nobody’s heart was really in it. McFarlane was pregnant and had planned to come off the road to raise a family, and drummer Seitan was recruited by The Turtles.

The band’s third album, Anything You Choose/Without Rhyme or Reason didn’t sell well despite its musical and harmonic sophistication and even though it included “Give a Damn.” And so, after playing out their concert commitments, less than four years after forming, Spanky and Our Gang were no more.

As for Mayor Lindsay, his path to reelection was difficult. Many seem to remember that he squeaked by, but in the end he won by a greater margin than his first run. In the run-up to the election, he lost the support of working-class Irish and Italian voters who felt that Lindsay’s advocacy on behalf of black and Puerto Rican voters came at their expense. Lindsay received overwhelming support from minority voters but still needed a voting block to put him over the top. He turned to the Jewish community, who he had disappointed in some instances, but who turned out for him at this crucial time.

Unfortunately for Lindsay, his second term was every bit as tumultuous as his first, marked by strikes of city workers, a lack of support from city law enforcement, and an increasingly negative financial situation for the city. He left office at the end of his second term in 1972, mere months before Gerald Ford issued his “Drop Dead” edict to New York City in regards to a possible federal bailout. By the time of his death in 2000, however, he was remembered as one of the city’s better mayors in terms of his concern for his constituents.

Paul Stookey of Peter Paul and Mary recorded a song of his own called “Give a Damn” that appeared on his first solo album Paul and, released in 1971 and as the B side of the single “Wedding Song (There is Love),” which Stookey also wrote. Stookey’s song makes fun of so-called limousine liberals who acted surprised that there were people in need of help in the city:

Then word got around that there’s this song

All about the riots and stuff

So, they played “Give A Damn” on the noon report

Just once, but that was enough

Some cameraman with groovy footage

Of glowing embers and charred remains

Put the pictures with the song on the six o’clock news

Following the baseball game

Then everybody said it was a real fine song

“Why didn’t we hear it before?

Let’s all blame the radio stations

For bringing on the domestic war

Oh sure, we’d seen some articles

We knew some people needed help

But social workers take care of that

I mean, why give a damn yourself?”

He challenges listeners to “address yourself to give a damn this summer.”

_____________________________________________________________________

The decade marched forward, ever closer to its end. The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour was abruptly canceled on April 9, 1969, supposedly over a failure to deliver a program on time for affiliate schedules, but that was clearly an alibi. CBS executive Robert Wood said that Tom and Dick Smothers “were unwilling to accept the criteria of taste established by CBS.”

The brief stir surrounding “Give a Damn” and the social movement it supported may seem like a tempest in a teapot compared to all that transpired in 1968. But by examining it we are treated to a microcosm of the forces that were at work in America in 1968: the forces that were spinning the country in a new direction and those that tried to keep that direction from becoming reality.

This is really good – so is your whole site.

Thank you, Bob. I appreciate your taking the time to read and comment on the articles. I really enjoyed researching ‘Give a Damn’ and it’s great to hear that it was an enjoyable read. Thanks again, and have a great day.

Thanks for taking the time to read the article and comment. I really enjoyed researching ‘Give a Damn’ and it’s great to hear that it was an enjoyable read. Thanks again, Bob, and have a great day.

I remember seeing an actual TV ad at the time as a child, or some kind of music video of the song, which basically depicted the lyrics by showing footage shot through the window of a ConRail commuter train as it pulls up to the 125th Street station. I’d be be curious to know anything about what it was I was seeing. I remember how shocking it was, because it was so unlike anything else on TV.

Hi, David. First off, thanks for visiting NDIM and taking the time to read and respond to an article. I am certain that I recall seeing the footage on the web somewhere when I was researching this article, but I cannot locate it anywhere now. I would not be surprised if it was a PSA by the NY Urban coalition. The ad they did entitled ‘Landlord” is up on YouTube, but I can’t find that one.