New Bottle–Old Wine and Great Jazz Standards collected together in Complete Pacific Jazz Sessions

by Marshall Bowden

Miles Ahead

On the first beautiful days of spring, the CD I find myself most invariably reaching for is Miles Davis’ Miles Ahead, recorded with a nineteen-piece band and featuring arrangements by Gil Evans. Recorded over several dates between May and August of 1957, Miles Ahead is most often noted as the recording that demonstrated the commercial possibilities of a Davis/Evans collaboration to Columbia Records, making possible the highly successful (both in terms of artistic merit and long-term sales) Sketches of Spain and Porgy and Bess.

But it’s a fine listen in its own right, and there is, I think, extra excitement in the knowledge that this was the first time Davis and Evans tried this. Evans had to construct skillful arrangements of the chosen tunes, which he arranged into suites with no gaps between songs. He had to allow space for Davis’ solos, but maintain tonal coloration that would complement the trumpeter without overpowering him. For his part, Davis had to carry the part of the only solo voice on the entire recording. He needed to play above the horn section and to keep his trumpet voice interesting to the listener. Even though the recordings were done on several dates and Davis also re-recorded segments of his solo that were ‘dropped in’ to the final recording, it still requires an artist with a good degree of stamina to achieve this.

One thing that is unique about Miles Ahead is the contrast between its lightness, in terms of overall texture, and its depth in terms of the levels of interest that are in play in Evans’ arrangements. It is not ‘light’ jazz nor lightweight. Some would question whether it is truly jazz at all, though listening to it today it seems to have all the elements of ‘cool’ jazz as defined by Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker, Gil Evans, and Miles himself. Even more introspective numbers such as “The Meaning of the Blues” achieve a certain lightness that makes them more melancholy than truly sad.

The music on Miles Ahead bristles with the energy of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, when small group jazz was entering its most fertile period. At the same time, it lays back with the gentleness and overall burnished sound of West Coast cool jazz. The harmonic explorations of bebop were well observed by these musicians, and they took the substitution of chords in standards of all kinds to be the standard operating procedure.

Gil Evans chose to use a big group, and his overall approach here owes a debt to Duke Ellington’s work. Ellington was still a major presence in the jazz world at this time, and he had pointed the way in terms of new ways of utilizing a large group of musicians that differed significantly from the approach of the big band swing era. Evans had been looking for ways to bring the big band into the modern jazz era since his work with the Claude Thornhill Orchestra. Evans studied not only the music of Ellington but also Don Redman and Fletcher Henderson, both of whom were innovative big band arrangers of their time.

Evans briefly led his own nine-piece band but then went into the army, where he played in various army bands. It was during this time that he discovered bebop, and it influenced him tremendously. In 1949-50 Evans wrote arrangements for the nonet that recorded the sides which eventually were collected under the banner of Birth of the Cool. These sessions also included Davis and Gerry Mulligan. From 1949-56 Gil Evans was relatively quiet, completing a few musical projects, but not a lot of real jazz work.

1957-1960 was an amazing time in the history of jazz music. In 1959 Davis would record the groundbreaking album Kind of Blue, while Coltrane would release My Favorite Things and Ornette Coleman would record Shape of Jazz to Come. The Dave Brubeck Quartet was playing concert halls and colleges around the world with their brand of jazz combined with oddly metered European-influenced compositions.

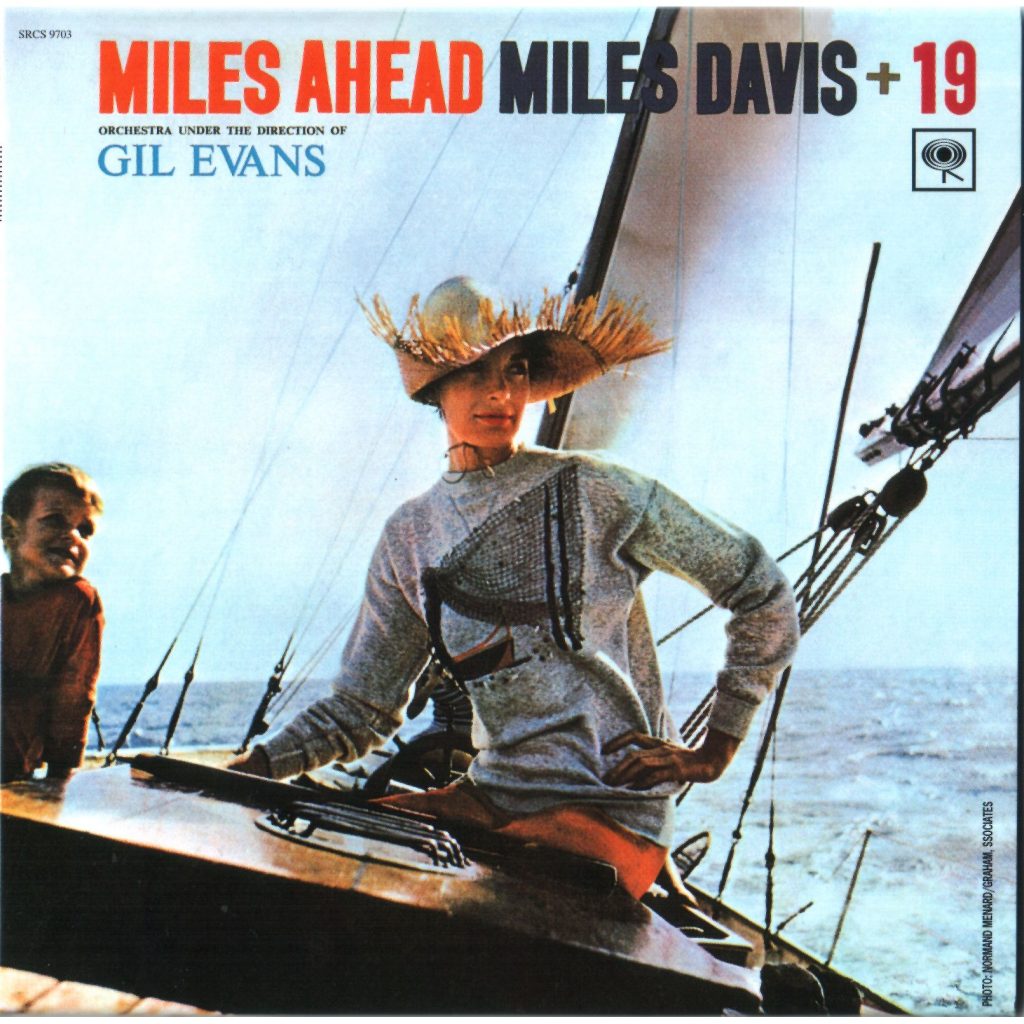

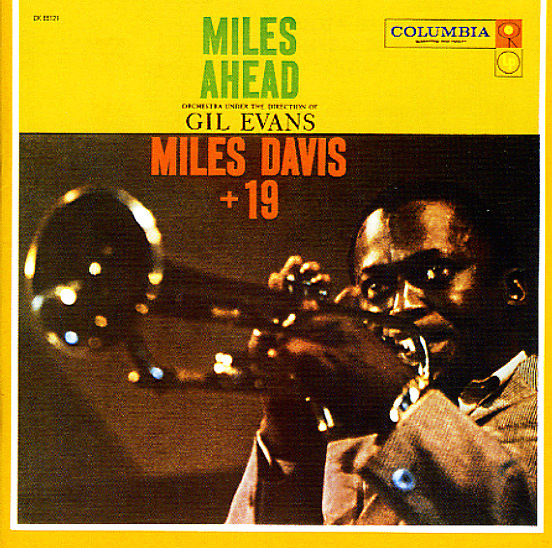

Young, sophisticated people were interested in these new sounds, and they purchased some of these albums. Columbia released Miles Ahead with a cover depicting a young white woman on a sailboat, wearing a straw hat and a sweater with a geometric pattern. The epitome of the lightness and coolness of the music inside, only Miles didn’t see it that way. He excoriated the record label for putting a ‘white bitch’ on the cover of his album, and subsequent pressings substituted a picture of Davis blowing his trumpet, eyes open and staring at the listener in seeming defiance.

The Golden Age of Gil Evans

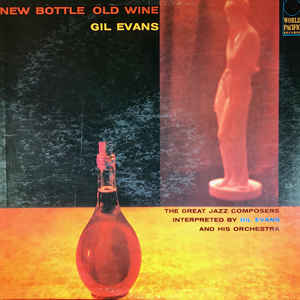

The period 1957-1962 was also the highlight of Gil Evans’ career. During this period he released a series of albums that included Gil Evans and Ten (released the same year as Miles Ahead), New Bottle—Old Wine, Great Jazz Standards (both 1958), Out of the Cool (1960), and Into the Hot (1961). Interspersed with these were the collaborations with Miles: Miles Ahead (1957), Porgy and Bess (1958), Sketches of Spain (1959), and the aborted Quiet Nights (1962).

The issuance of Evans’ two 1958 releases, New Bottle—Old Wine and Great Jazz Standards on a single CD entitled Gil Evans: The Complete Pacific Jazz Sessions reveals that Evans could work magic with musicians other than Miles. The featured soloist on New Bottle—Old Wine is Cannonball Adderley, who would also distinguish himself on Kind of Blue, not to mention his own Davis-produced session, Somethin’ Else, recorded the same year as New Bottle.

Adderley’s bright alto sound is in sharp contrast to Miles’ more melancholy trumpet, and the concept here is quite different. Evans tackles nothing less than a kind of history of jazz music, presenting arrangements of “St. Louis Blues,” “King Porter Stomp,” Fats Waller’s “Willow Tree,” “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue,” “Lester Leaps In,” “Round Midnight,” “Manteca,” and Charlie Parker’s “Bird Feathers.” Many of these tunes are decidedly ‘hot’ in nature, but Evans’ arrangements manage to display a ‘cool’ palette even though there is never a lack of energy.

Related: Three by Cannonball Adderley

The tunes are given modern harmonic orchestration, and Evans certainly displays sensitivity towards the music itself, as evidenced by this observation from David Baker’s liner notes, written for a 1975 Blue Note reissue of these albums (speaking of ‘King Porter Stomp’):

“As with the earlier King Oliver version, Gil chooses to accent the sectionalized nature of the composition via brilliant and highly differentiated orchestration. (I can’t help but feel that were Jelly Roll scoring the piece today, he might have done it this way.)”

Evans himself plays piano on these recordings, often making the listener wish he would play more, as on the introduction to “Willow Tree.”

David Baker, Liner Notes, Great new bottle–old wine by Gil Evans

The remaining seven tracks on The Complete Pacific Jazz Sessions—“Davenport Blues,” “Straight No Chaser,” “Ballad of the Sad Young Men,” “Joy Spring,” “Django,” “Chant of the Weed,” and the Evans original “La Nevada (Theme)” come from the followup album Great Jazz Standards. Recorded in 1959, this album doesn’t feature Adderley, and indeed features several different soloists rather than relying on a single instrumental voice to carry the recording. Trumpeter Johnny Coles solos on the Bix Biederbicke piece “Davenport Blues,” while Monk interpreter supreme Steve Lacy solos on “Straight No Chaser.” Other musicians contributing to this effort include Curtis Fuller, Jimmy Cleveland, Bill Barber, Al Block, Ray Crawford, Tommy Potter, Budd Johnson, and Elvin Jones.

Evans continued to record under his own name as well as working with artists such as Kenny Burrell and Astrud Gilberto. He eventually became very interested in the work of guitarist Jimi Hendrix and recorded a couple of albums dedicated to interpretations of Hendrix’ music.

Gil Evans’ place in jazz history is secure, even if albums such as the two collected on The Complete Pacific Jazz Sessions as well as recordings like Out of the Cool and Into the Hot have not really received the attention they deserve. It is his work with Miles that will always be most remembered, at least in part because of the enduring popularity of Miles Ahead, Sketches of Spain, and Porgy and Bess in the Davis canon of recorded work.