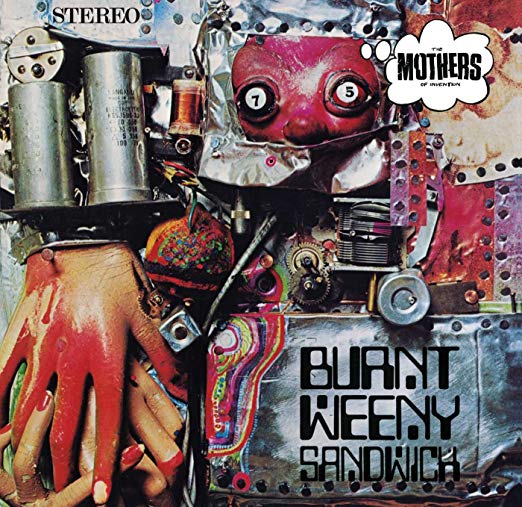

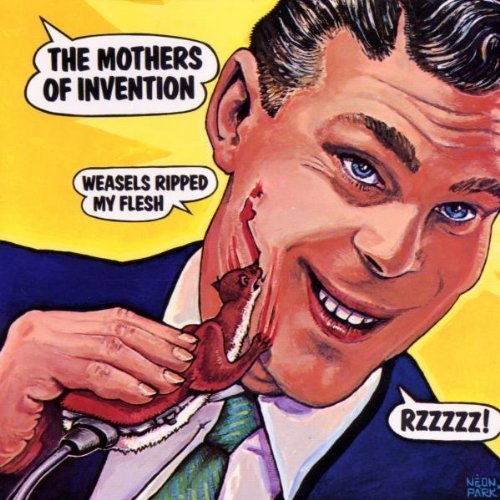

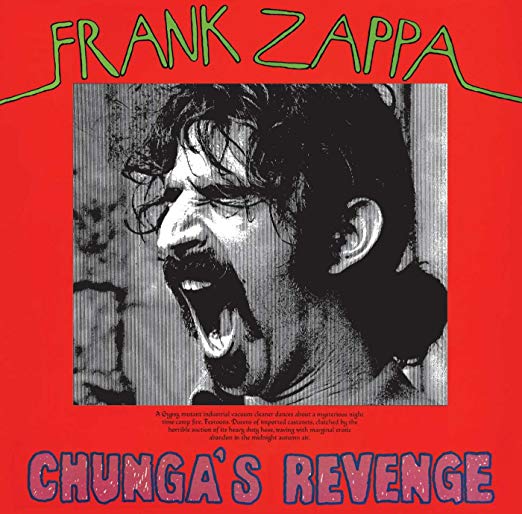

Frank’s three releases in the year 1970 consisted of Burnt Weenie Sandwich and Weasels Ripped My Flesh, recordings by the original Mothers of Invention tweaked and edited by Zappa, plus Chunga’s Revenge, which bridges the gap between the old Mothers and the new version of the band that Zappa would soon unleash.

by Marshall Bowden

One of the first things that any self-respecting Zappa fanatic will tell you is that Frank Zappa didn’t do drugs. At all. He reportedly smoked pot once and didn’t like it. He drank only rarely. His comments about drugs and other accouterments of the counterculture lifestyle could just as easily apply to today’s social media laden environment:

“All this stuff not only give you a physical sensation, it gives you a social sensation; it gives you the impression that you have social worth in a certain circle of friends because you have all the mannerisms of a certain lifestyle and because that is different from certain other lifestyles you must therefore be better. It just tends to emphasize feelings of self-worth in instances of people who might not have too much self-worth and need some.” (John Corcelli, Frank Zappa FAQ, Backbeat Books 2016)

Yet when I hit high school at the start of the ’80s, Frank Zappa was hugely popular with burnouts. I should say that he was popular with burnout guys. Burnout girls much preferred Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant or Jimmy Page. In fact, girls of all stripes pretty much hated Zappa’s work.

The group of guys who love Frank Zappa is a group of mostly male non-conformists, outsiders even in the ways that they are outsiders: music geeks, serious musicians, computer geeks, guitar freaks, perverts, future standup comedians, incels, libertarians. They like Zappa for various reasons: his anti-censorship stance, his guitar solos, his compositions, his arrangements, his humor and satire, and…wait for it…his intense, immature obsession with sex. The weirder the better.

Zappa was obsessed with sex and with groupies–a term he coined–and the relationship between the women who followed him and his band, the Mothers of Invention on the road. The sexual politics of that relationship seem to have either been lost on him or purposely ignored. But the topic of sex with women fans, the stories of sordid backroom couplings and erotic contests and mud sharks–all of that is a continual source of lyrical inspiration on Zappa’s work throughout his career.

Sometimes it gets in the way of what is otherwise a perfectly good record. But Zappa couldn’t limit himself to just making a certain type of music or playing his guitar solos or doing whatever might possibly have brought him more fame and fortune than he enjoyed during his lifetime. He was going to do serious 20th Century composition, he was going to do free jazz, he was going to do rock and roll boogie, he was damn well going to do rhythm and blues and doo-wop. And he was going to write about groupies and sex frequently because that was a large part of his life, married or not.

By 1969 Zappa had built his own studio in a complex in the Hollywood Hills and moved away from the social scene that had prevailed at his famous home known as the Log Cabin in Laurel Canyon, where in 1968 he’d been accosted by a young woman with a baggie full of blood and a gun. Having broken up his band, the original Mothers, he proceeded to record Hot Rats, an almost entirely instrumental album that opened new vistas for Zappa.

Hot Rats achieved the apotheosis of rock, blues, modern jazz, avant-garde classical, and humor that he had been working toward with the Mothers. He recorded most of the album with multi-instrumentalist Ian Underwood who had joined the Mothers for their third album, We’re Ony In It For the Money and remained with Zappa until 1973. Using a specially built sixteen-track recorder (Zappa referred to it as ‘homemade’) he was able to add instrumental texture to the music and create the sound of a larger ensemble with only a few musicians.

Hot Rats was very successful for Zappa both critically and in terms of sales and exposure. It was a blueprint for what would become Zappa’s most well known and influential work through the decade of the ’70s.

Unfnished Business

But there was still unfinished business with the Mothers of Invention.

The original Mothers of Invention ended for a lot of reasons. At least one of those (and the one Zappa cited) was financial. The group wasn’t selling a lot of albums and as a touring act they had a lot of overhead. There were other issues as well. The band seemed to feel like Zappa was keeping himself apart from the band by staying in separate hotels while on tour and his penchant for perfection could rankle the other musicians.

Zappa himself was moving away from the heavy duty social commentary found on Freak Out and We’re Only In It For the Money. He composed a great deal of instrumental music for the Mothers’ live performances and wrote intricate arrangements for them. He felt this was the direction the band was going, but audiences were often confused by this since the group’s recorded output at that time consisted of many vocal tunes.

Making matters worse, audiences made it clear that what they really wanted to hear was more guitar solos by Zappa. Zappa was always well regarded as a guitarist, though he definitely improved a great deal through the 1970s until he was formidable.

“Once I get out onstage and turn my guitar on, it’s a special thing to me -I love doing it” he told Guitar Player in a 1977 interview. “But I approach it more as a composer who happens to be able to operate an instrument called a guitar, rather than “Frank Zappa, Rock and Roll Guitar Hero.”

In any event, following the release of Hot Rats and the dissolution of The Mothers of Invention, Frank Zappa released two records of material culled from recordings the Mothers made between 1967 and 1969: Burnt Weenie Sandwich and Weasels Ripped My Flesh.

Burnt Weenie Sandwich and Weasels Ripped My Flesh

Taken together these albums are kind of an Odds and Sods-like compilation of music recorded both live and in the studio by the original Mothers of Invention between 1967 and 1969. But Zappa has clearly spent a good deal of time selecting and producing these tracks for release, and the albums give much more of a sense of cohesiveness and of the group’s musicianship and Zappa’s compositional abilities than the more expansive 1969 Mothers release Uncle Meat.

Uncle Meat may have been burdened by originally being conceived as a soundtrack to a science fiction film that was never made. Zappa indicated that the album was part of a Wagnerian cycle along with We’re Only In It For the Money and Ruben and the Jets. Though it contains much of Zappa’s serious avant-garde work as well as some pieces influenced by free jazz, the tracks are shorter and come across less as just music and more as part of a program.

But Zappa may have wanted a chance to present some of the music he had written over the past two years without programatic constraints and these two albums do that. There are themes that recur from some earlier work just as the Hot Rats track “Son of Mr. Green Genes” was turned into a fusion anthem inspired by the vocal track “Mr. Green Genes.” Burnt Weenie Sandwhich in particular comes across as a more focused and carefully edited Uncle Meat.

Knowing he wasn’t going to work with this group of musicians again had to be difficult in many ways. Zappa had worked with these musicians and taught them how to play his music. Musicians work hard to learn the music their leader writes or arranges and this creates a bonding experience. Napoleon Murphy Brock, who joined Zappa’s Mothers in 1973, describes the process:

“Zappa’s compositions are damnably difficult music. The harmonies are continuously changing, while the tempos are totally surprising. At the time, I had no idea about any of it. I had never had such a tough time as then…I made myself scarce with my saxophone and practiced day and night. I was almost in despair. Then I got the buzz and slowly started to understand Zappa’s musical universe.” (On Tour With Frank Zappa, Spiegel International, 10.98.2009)

The first side of the vinyl edition of Burnt Weenie Sandwich consists of several shorter compositions that highlight Zappa as a serious composer, though his humor pokes through in places–the drunken, over-vibrato saxophone section on “Holiday in Berlin” or the tape speed experiments of “Theme from Burnt Weenie Sandwich.”

“Igor’s Boogie” is presented as two thirty-five second tracks of chamber wind ensemble music that pays tribute to the closest thing to an idol Frank Zappa ever had, Igor Stravinsky. These encapsulate the tracks “Overture to a Holiday in Berlin” and “Holiday in Berlin” which in turn cradle the tender meat of “Theme from Burnt Weenie Sandwich.” The side concludes with “Aybe Sea,” a showcase for Ian Underwood’s piano work as well as some nice, rare acoustic guitar work from Zappa.

Underwood is an underrated pianist and I’ve always thought this track sounded a bit like a ’70s ECM record, though I somehow doubt Zappa would find that complimentary. Underwood is featured again on the lengthy “The Little House I Used to Live In” with a solo that goes even deeper into jazz territory. The eighteen-plus minute track features a series of variations on a theme, with another breakout section comprised of a searing solo by electric violinist Sugarcane Harris.

The track became a popular live one largely because it’s a jam band tune, with some changes of mood, character, and intensity but plenty of room for the principal soloists (Harris and Underwood) to do their thing. There are moments on “Little House I Used to Live In” where you can clearly hear the influence of Hendrix, of free jazz, of blues rock and it’s just a joyous act of creation. That’s the thing that a lot of Zappa fans listen for, the moment where there is liftoff and the magic happens, kind of like that zone that Deadheads get into during a particularly good Grateful Dead set. But of course, with Frank Zappa there is no whiff of the psychedelic, no haze of weed hanging over the proceedings–well, not for the musicians anyway. For his listeners, it may often be a different story.

Burnt Weenie Sandwich begins and ends with Zappa’s carefully done pastiches/tributes to doo-wop and early rock and roll. “WPLJ” (which stands for white port lemon juice) was recorded by Salinas doo-wop group The Four Deuces) while the closer, “Valerie” was the only hit record (in 1960) for Jackie and the Starlites.

Weasels Ripped My Flesh is often characterized as more of a ‘free jazz album’ but I find it to be more of a grab bag and less cohesive overall than Burnt Weenie Sandwich. It’s divided pretty evenly between tracks recorded live and those done in the studio–sometimes it’s difficult to tell which is which until you hear applause at the end.

So even though the opening track “Didja Get Any Onya?” sounds like a free blowing session for a while it eventually becomes an experiment in vocal sounds that is reminiscent of serious avant garde compositional experiments, which we again hear on “Prelude to the Afternoon of a Sexually Aroused Gas Mask.”

In between, we are treated to a straightforward blues-rock rendition of Little Richard’s “Directly from My Heart to You” with violin and vocals by Sugarcane Harris. Zappa makes fans of his guitar work happy with “Get a Little.” “Eric Dolphy Memorial Barbecue” features the marimba playing melodic lines in a manner Zappa had been employing since Uncle Meat with Art Tripp and Ruth Komanoff (later Underwood) playing the marimba lines. Ruth Underwood would later play on classic Zappa work like Apostrophe and One Size Fits All.

Although Weasels Ripped My Flesh is a more ‘difficult’ album to listen to, frequently changing moods and styles and with some cacophonous passages it has a lot of great music. Towards the end of the album, Zappa slips in a great rock number (“My Guitar Wants to Kill Your Mamma”) and a fusion number (“Orange County Lumber Truck”) that ends with a chugging guitar solo. The album concludes with the title track, two minutes of sustained group feedback that ended a live European performance.

Chunga’s Revenge

Chunga’s Revenge was released as a Frank Zappa record, making it the followup to Hot Rats. Even so, the album is essentially a transitional one taking Zappa from one incarnation of Mothers of Invention to the next. The groups that followed the original Mothers of Invention were far different than the original group. Zappa retained the band name although he generally referred to the later versions of the group as simply The Mothers. This was reputedly the name he wanted for the original band but which was rejected by the record company.

The vocal numbers here (which, except for the bluesy “Ladies of the Road” are the most pop-oriented songs on the record) feature the team of Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan, who had previously been with the pop-rock band The Turtles. They would become an integral part of The Mothers in their next major period.

Unfortunately, these songs were a preview of things to be expected on the forthcoming 200 Motels album, which itself would be the soundtrack to a film of the same name. The topic of all of these songs are bands on the road and sex with groupies and they are the type of thing I referred to earlier as getting in the way of a perfectly good record.

Having been rewarded with moderate critical and consumer interest in his music with Hot Rats, Zappa veered in a direction that was part of his overall plan and which appealed to him but which alienated some older listeners and didn’t bring him many new ones. Zappa also pulled back from social commentary and moved towards lyrics that told stories full of surreal characters and situations with a wry, cynical sense of humor.

Even though this album is less of a hodgepodge in terms of the time frame, with most of it recorded over a year or so, there is a difference in bands. Among the most interesting tracks here are two instrumentals that provide a base for extended Zappa guitar solos: “Transylvania Boogie” and “Chunga’s Revenge,” chosen from material Zappa played with Ian Underwood, Aynsley Dunbar, Sugarcane Harris, and Max Bennett, a group he referred to briefly as “Hot Rats” although they never recorded. Another track, “Twenty Small Cigars” is a mellow jazz interlude with Bennett and Max Guerin, Ian Underwood at the piano, and Zappa playing guitar and harpsichord.

The aforementioned tracks are really all one needs from Chunga’s Revenge. In the words of Robert Christgau:

“Zappa’s aestheticism intensifies his contempt for rock and its audience. Even Hot Rats, his compositional peak, played as much with the moods and usages of Muzak as with those of rock and roll. This is definitely not his peak. Zappa plays a lot of guitar, just as his admirers always hope he will, but the overall effect is more Martin Denny than Varese. Also featured are a number of ‘dirty’ jokes.” (Christgau’s Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981) )

Zappa’s new Mothers would complete the minor fiasco 200 Motels plus a couple of live albums in 1971. In 1972 he would release his next solo record Waka/Jawaka, and an album featuring the next version of The Mothers, The Grand Wazoo. Volman and Kaylan were gone and Zappa had recruited a number of new musicians who were technically proficient as well as having strong voices on their instrument. The Grand Wazoo sparked a period of high creativity for Frank Zappa and The Mothers with 1973’s Over-Nite Sensation and 1974’s Apostrophe.

Burnt Weenie Sandwich and Weasels Ripped My Flesh are both excellent albums highlighting some great playing by the original Mothers of Invention. The care that Zappa put into the editing of these albums demonstrates that he felt they were important musical statements in their own right regardless of what direction they may have led in.