The age of vinyl was the heyday of artistic album covers and album covers as art.

by Marshall Bowden

The death of Pedro Bell, the artist behind the iconic album cover art of Funkadelic, made me think a lot about vinyl album covers. When I was starting New Directions in Music, I decided that I wanted to do a regular feature on people whose artwork appeared on various album covers.

We all know about some of the more iconic album cover art in history and the artists who created them, but there are many more covers that catch our eyes or are by favorite artists where we really don’t know about the artist or creator at all. Nearly everyone recognizes the image on the cover of In the Court of the Crimson King–even if they are unfamiliar with the music itself–but few will know that the image was painted by Barry Godber, a friend of Crimson lyricist Peter Sinfield, and that it is the only album cover he ever designed.

Similarly, the general public knew little about Pedro Bell or his work, and even a lot of music listeners didn’t realize the extent to which he helped shape Funkadelic’s overall presentation and mythology.

Whether the creator is a graphic artist like Bell or Godber or Mati Klarwein (who created the images used on Bitches Brew and Abraxas) or a photographer like Eliot Landy or Pete Turner, their work is recognized nowadays as part of the artist’s branding, and it is given more respect as both commercial and fine art.

Record labels initially used branding to make their records stand out or to make an aesthetic statement. That makes sense because a record label is a company, and branding is an essential component of a successful company. The label designs and logos that they used defined the company as much as their tag lines and print ads.

The classic Capitol label with its image of the U.S. Capitol dome flanked by four stars as well as their signature yellow and orange swirl 45 rpm label, the Columbia ‘eyeball’ seen in various configurations through the years, the A&M trumpet logo on a gold label–these were as common and iconic to Americans in the 1950s and ’60s as the logos of Zenith or IBM.

Some independent label owners began to see the value of extending their branding to the album cover art itself. This was especially true in the jazz field. Creed Taylor developed a presence for Impulse! that included an orange spine, cover fonts and the work of a certain group of photographers, all designed to make his label’s records stand out both in record shops and on the record buyer’s shelf. Taylor was partially inspired by existing jazz labels such as Blue Note, who used the photography of Francis Wolf to solidify a brand and give the listener a definite feeling about the kind of music that was likely to be found inside.

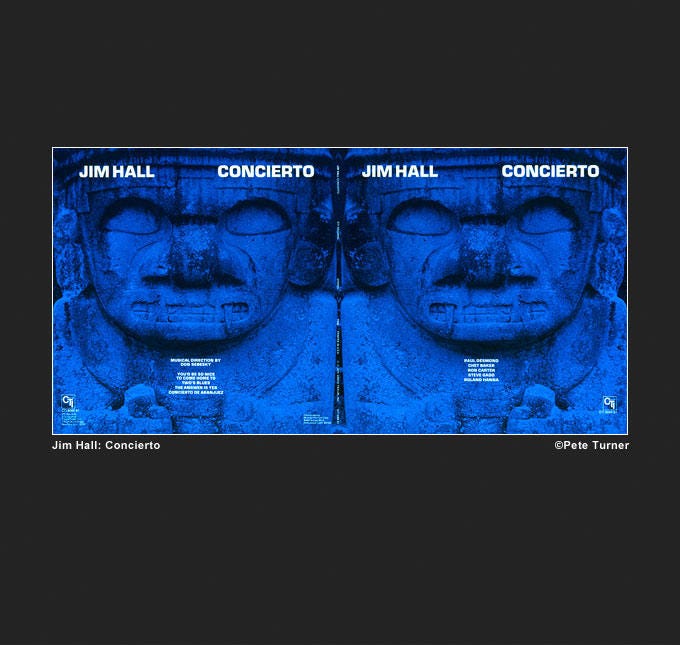

Taylor did this again when he started CTI Records, but here the idea took another step forward with regard to the album cover art. Most CTI releases featured the photography of Pete Turner in a glossy reproduction that took up the entire cover. Turner’s photographs weren’t images of the musicians or abstract work meant to give a jazz feel to the cover. This was art photography that was given a full showing on the cover. Turner’s subject matter was often wildlife found in exotic climes such as Africa or South America.

It’s interesting to note that it was Turner who noted that Taylor was responsible for creating jazz albums that stood out visually, as he recollected in this interview on Marc Myers’ award-winning jazz blog JazzWax:

“On the weekends, when I was in the army, I used to go into Manhattan. I’d take photographs for my portfolio and then go to record stores and look through the bins. I thought record covers were pretty interesting. Each time I’d run through the albums I’d see head shot after head shot on the covers. But every so often, an album cover would stand out. When I’d turn the album over to see what was going on, the album had Creed Taylor’s name on the back…”

Manfred Eicher used the same approach when he started his ECM (Edition of Contemporary Music) label in Munich in 1969. Eicher also made striking imagery–sometimes photographs like Turner’s, other times modern art or abstract shadows and light–the main feature of his album jackets.

These labels made each of their releases something like an issue of a magazine. The contents were different, but the packaging was familiar, a known entity that gave the record-buying public a framework for what to expect when they put the record on. Even the name of Eicher’s offering–Edition of Contemporary Music–suggests the magazine model.

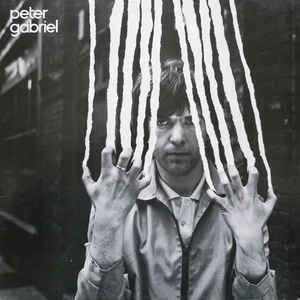

When Peter Gabriel began releasing solo albums after leaving Genesis, he used the idea of a magazine outright. Each image (retouched and with effects added) of Gabriel is accompanied by nothing more than his name. The first three albums are all named Peter Gabriel, but each is a different issue from his brand. Eventually, the albums became known by descriptions of the cover art–Car, Scratch, Melt–rather than official titles.

Not coincidentally, the Gabriel covers were all done by Hipgnosis, the British design firm founded by Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey Powell. They began their run in 1973 with the cover for Pink Floyd’s Saucer Full of Secrets and continued to design covers for Pink Floyd, Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, Bad Company, Scorpions, ELO, Al Stewart, The Police, and many more. It’s incredible now to think that there was a design house that focused pretty much exclusively on album covers, but Hipgnosis was a success largely because Thorgerson and Powell understood that the album cover art was an exercise in branding and that branding now extended to each and every release by a major musical act.

Hipgnosis dissolved in 1983, the same year that Compact Disc players and CD media were introduced in Europe and North America, symbolic because the coaster-sized CD case is commonly seen as the end of the era of creative and innovative album cover design. But cratediggers still enjoy finding album covers that are often more interesting to them than the music within, and holding a copy of a CTI album or Dark Side of the Moon or One Nation Under a Groove feels like holding a Van Gogh or a Picasso–it’s a direct physical link to the person who created it and it helps to transport the listener–along with the music–to another point of view and often another universe entirely.