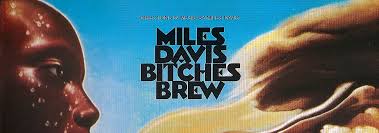

Back in 2006 when the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inducted Miles Davis, there were more than a few raised eyebrows. Davis did release some heavily plugged-in music beginning with the album Bitches Brew, but many still never saw him as a rocker. But Miles didn’t just transform jazz, he transformed and was transformed by rock, funk, and soul music and ultimately popular culture as well.

Here are 8 reasons that Miles Davis belongs in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame:

1. Using the studio as a musical tool

Like everyone else in the 1960s, Miles saw the way the Beatles and producer George Martin used the studio to create their music. Many rock artists began to follow suit, but in jazz the idea was completely alien. Jazz musicians were pretty much committed to laying down their tracks live in one or two tries, with no overdubbing, edits, or effects. Miles said forget that noise. He and producer Teo Macero began to edit together pieces from studio sessions that involved large groups of musicians, making Miles’ records more like Sgt. Pepper’s than Kind of Blue.

Macero pioneered techniques that elevated the recording studio into more of a creative and artistic tool than it had ever been before. In his later work with Miles Davis, he was helping the trumpeter build compelling narratives and integrated, composition-like works from what had in some cases been little more than passing fragments of improvised inspiration.

The genius of Macero’s editing on Bitches Brew and his larger role in Miles’s electric music can be compared to that of George Martin’s work with The Beatles. Like Martin, Macero often added a classical music sensibility to Miles’ music, and worked with him over a long period of time (from 1958 to 1983).

Being in the same category of studio innovation as artists like The Beatles and the Beach Boys certainly qualifies Miles Davis for the Rock Hall of Fame.

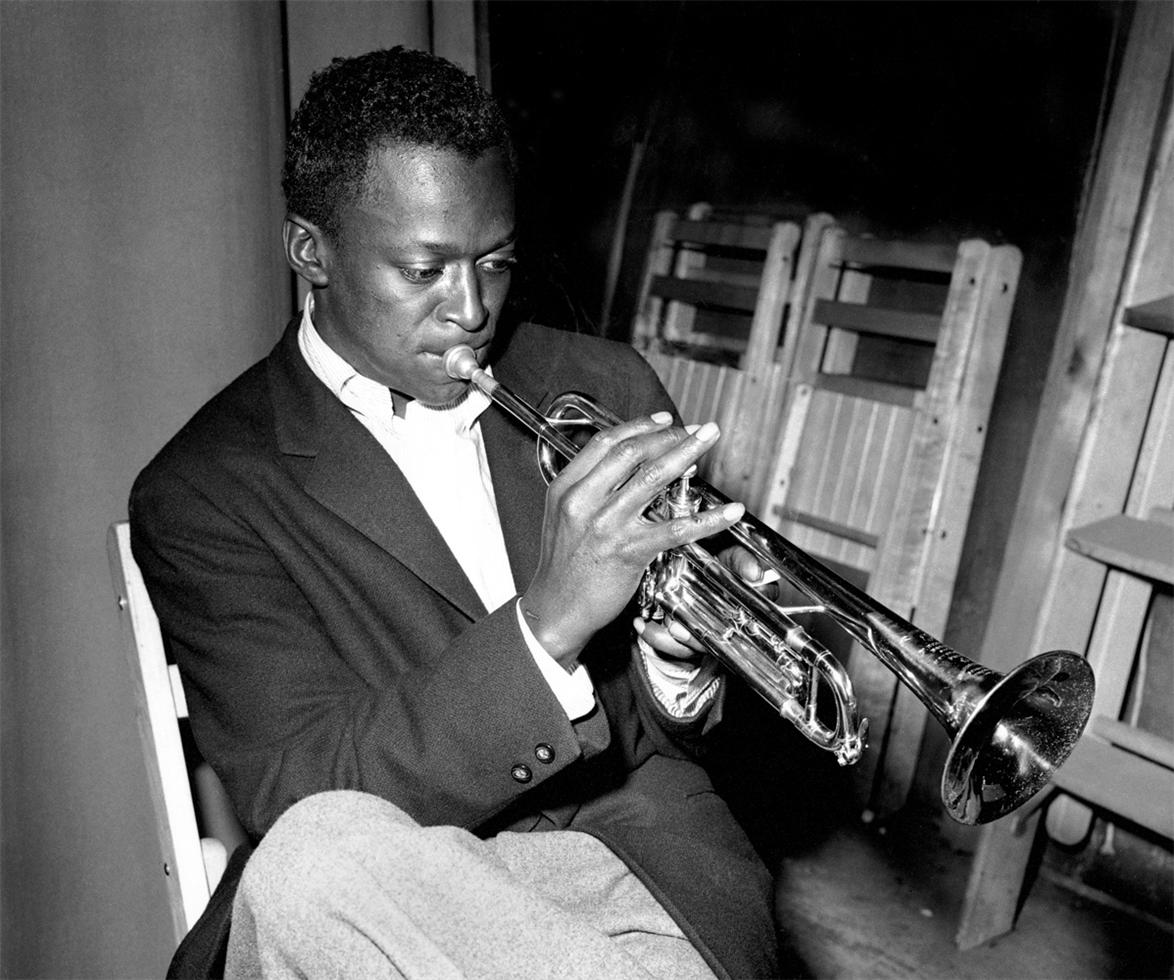

2. The importance of style and fashion

Miles was always known for being well-dressed and having an interest in clothes, and his image was always clustered around what was new, sleek, and modern. Influenced by then-wife Betty Mabry and rock guitarist and clotheshorse (and future Rock Hall of Famer) Jimi Hendrix, Miles began to dress like a Carnaby Street dandy rather than an African-American jazz musician from East St. Louis. He knew that to be a rock star, you have to dress the part.

Gersha Phillips, the costume designer who also made all the clothes for “Miles Ahead,” including a kimono in habutai, did not know how fashionable the trumpeter was until she started her research.

“I was quite amazed,” she said. “I just feel like he was always forward-thinking, and just the way he was with his music he was with fashion: ahead of his time.”

3. He instinctively understood rock music and musicians

When Miles was influenced by rock artists, he was influenced by some of the best. His initial electric period was ushered in by his interest in Jimi Hendrix. In later years, following his five year retirement period, he became interested in the music and image of Prince. According to biographer Ian Carr, he was damned near obsessed with the leprechaun of Paisley Park.

Miles had a great eye and ear for musicians that were going somewhere, and he brought them into his bands, where they matured and then left to do their own thing, usually becoming pretty well-known in their own right. Critics and fans sometimes complain that these bands didn’t have the musical acumen of his older, jazz-playing combos, but they ultimately can’t argue with the talent these musicians did turn out to possess.

Yet if these be the children of Miles, one peculiarity must be noted–pretty good or very bad, their fusion doesn’t sound much like papa’s. Without the hint of a doubt, they all compose, they all arrange, and they all solo to beat the band.

Robert Christigau

4. Black Power movement

“White people have certain things they expect from Negro musicians — just like they’ve got labels for the whole Negro race,” said Davis in a 1962 Playboy interview.

Make no mistake: Miles was hip to the changes that were in the wind by the early 1970s with regard to the Black Power Movement. Miles himself was not directly involved with groups like the Black Panthers, but his music became much more reflective of the black urban experience. In addition, he went into the studio and created an album of music for the film documentary A Tribute to Jack Johnson, about the black heavyweight champion who rankled many whites with his unapologetic blackness.

But the trumpeter’s larger reaction to racial inequality was more personal. He refused to defer to his audiences, turning his back onstage for entire concerts and neglecting to speak to them onstage or off. While he did this for both black and white audiences, he intensified his contempt for the latter. Davis even criticized his heroes Gillespie and Louis Armstrong for their willingness to mug for the white crowds (“tomming,” as Davis called it). Still, he demanded respect from the white music industry, strongly asserting himself on issues of payment and ownership — a concern reflected in “Miles Ahead.”

5. Sun City

In 1985 Little Steven Van Zandt of Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band was putting together a recording of a song he’d written and planned to release as a single. The song was called Sun City, and it was a protest of the resort located in Bophuthatswana, one of several regions where various ethnicities of black South Africans were forcibly relocated by the apartheid South African Government.

Van Zandt wanted a massive list of rock performers to contribute to the recording. Most of the artists recorded separate tracks in the studio that were combined to create the finished song. Artists that Van Zandt reached out to included Bruce Springsteen, Jackson Browne, Gil Scott-Heron, Lou Reed, Joey Ramone, Ringo Starr…and Miles

“The same thing happened with Miles Davis. I had a part for him on the intro, just a few seconds, but he played for seven minutes. There I was using five seconds on the song, and I thought, ‘I can’t leave six minutes of Miles on the floor!’ So we got Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams and Ron Carter and put together a jazz version.”

Steven Van Zandt

In addition to the jazz number and the “Sun City” single, Davis also appeared on several other of the album’s tracks, including the galvanizing rap collage “Let Me See Your I.D.”

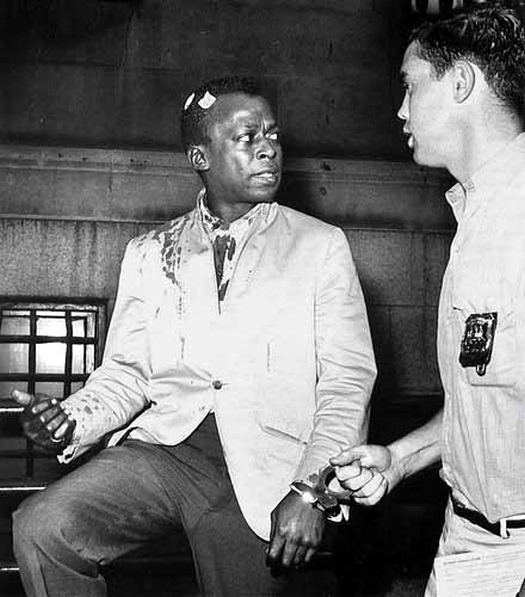

6. Police on my back

One late August night in 1959, Miles was playing at Birdland. Between sets, he escorted some friends to a cab and stopped to smoke on the sidewalk outside. A police officer came by and ordered Davis to clear the sidewalk. Davis, feeling that he was being harassed because he was African American, refused. In the ensuing melee, Davis was bloodied after being hit by a detective with a blackjack. He was arrested and arraigned. Photographs taken at the scene show Davis’ bloodied head and suit jacket.

Davis was pulled over on traffic stops fairly often while driving his Ferrari, and the title track of his 1985 album You’re Under Arrest features rocker Sting reciting the Miranda warning in French.

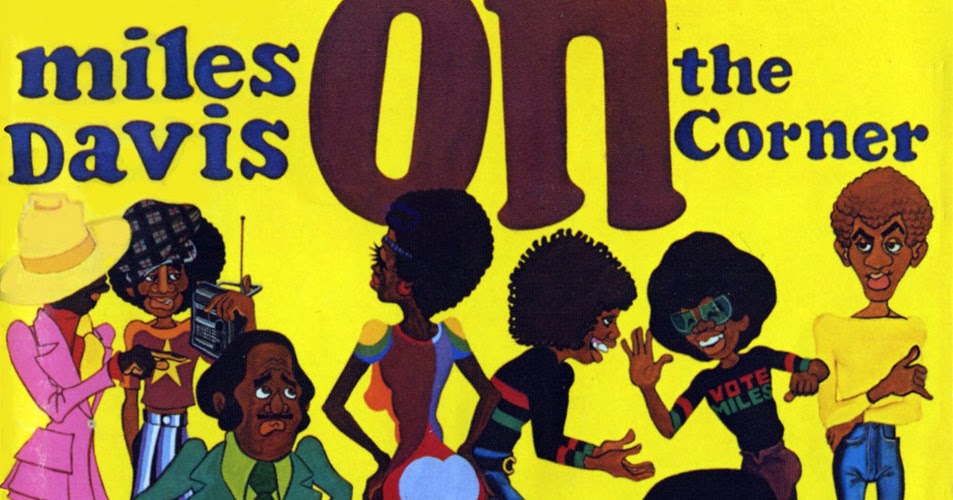

7. Super cool album covers

In the 1960s and 1970s, if you wanted to have a badass album, you needed a badass album cover. Jazz album covers tended to be rather generic and non-controversial, often depicting a photo portrait of the musician or perhaps simply the pertinent information—artist, title, sidemen—against a generic background.

Beginning with Bitches Brew Miles’ cover art took a more modern art/psychedelic rock and roll turn. For that artwork, Davis commissioned Mati Klarwein, an artist who was living in New York City at the time and who also created the painting “Annunciation”, part of which was used as the cover for Santana’s Abraxas. Klarwein’s work was also used for Miles’ album Live/Evil.

Davis’ 1972-1975 period was marked by a move toward album art that was more reflective of the black urban experience. Artist Corky McCoy produced a cartoonish take on urban life for the cover of On the Corner, and his work was also used for the album Water Babies.

8. Sunglasses

Throughout his career, Miles showed a penchant for sunglasses. Ever present, they ranged in style from the Rayban style of his Kind of Blue days through the darker, bigger shades he sported from the time of Bitches Brew on—some round, some rose colored, some octagonal. The shades were always there, always part of Miles’ super cool image.

And cool shades are one way that rock and rollers, rebels, and outcasts have always distinguished themselves from the squares that surround them. So of course Miles Davis belongs in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, though it’s doubtful Miles himself would have been overly impressed by his inclusion.