Read Luciana Souza: The New Bossa Nova

by Marshall Bowden

Luciana Souza is a singer who takes more than a passing interest in the words that she is singing. Previous projects have revolved around poetry and literature: The Poems of Elizabeth Bishop and Other Songs (2000) and Neruda (2004) were based, respectively, on the work of Elizabeth Bishop, an American poet who lived in Brazil for nearly two decades and Chilean poet Pablo Neruda.

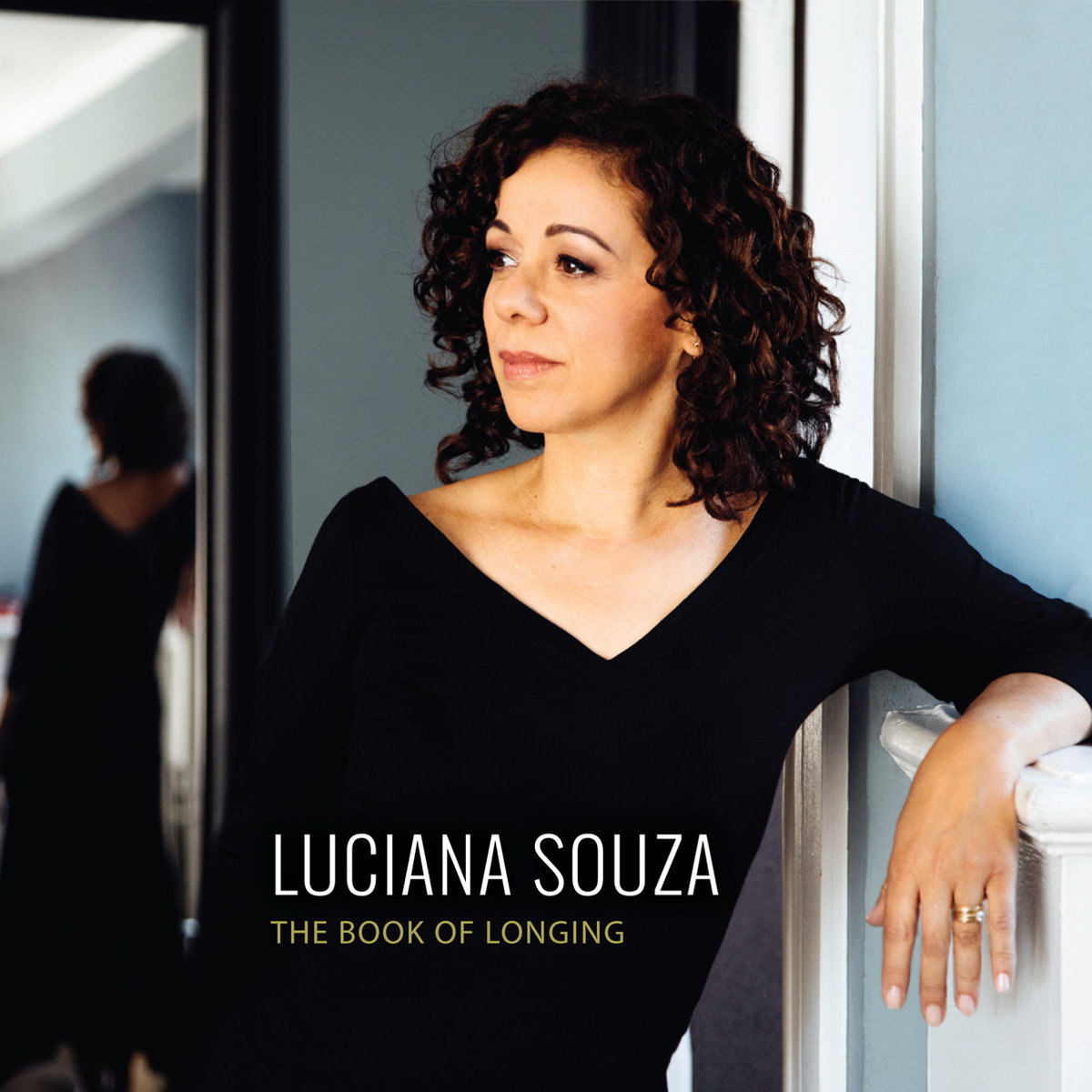

Souza’s newest album, The Book of Longing takes its title from Leonard Cohen’s 2006 collection of poetry. She sets the titular poem to music in a track called “The Book.” She adapts Cohen’s tribute to departed singer Carl Anderson, “Nightingale” as “Night Song.” She also takes on Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Alms”, a sweet melancholy poem about the seasons of love, Emily Dikinson’s “We Grow Accustomed to the Dark,” and Rosetti’s “Remember.” And there are four of Luciana’s own lyrics set to music that is conceived and arranged by her.

The arrangements are spare and intimate, utilizing the light but varied work of Brazilian guitarist Chico Pinheiro and the grounding yet elastic bass of Scott Colley. Souza adds some touches of percussion herself to a number of tracks, adding tonal color and texture.

“Literature has been present in my life through everything I do,” she said in a recent interview. “ My mother was a poet and so many lessons she taught me were imparted through lines of poetry. My life is marked by poetry. The Bishop album began mostly as an exercise at home, and it grew from there. Words and language are a way for me to get to other things.”

Poetry and music are inextricably linked and always have been. There is music in poetry, unquestionably. Sometimes it breathes forth like a giant string section, at others it is as reserved as an oboe solo. It can even be harsh, discordant, but still it is music. There is also poetry in music, often in the lyrics which may have poetic constructs, but also in the notes themselves.

One reason for this is the fact that both are meditative acts. The creation of any art force is often said to be the work of a creative force, not of the singular artist. Both poets and musicians seek to express the inexpressible and to demonstrate the universality of the human experience.

The whole point of meditation isn’t to stop the mind from thinking, which is impossible, but rather to control its reaction to events and people so that one can examine and understand the darker, more painful experiences one has. It’s no conincidence that Souza works with four sets of lyrics by the late Leonard Cohen. Besides being a consumate poet, Cohen sequetered himself in a Zen monastery for six years, meditating for several hours a day,

The Book of Longing is an exquisitely rendered meditation on love, on the difficulty of human relationships, on comings and goings and the longing that one’s soul feels during the course of a lifetime. And, inevitably, on the approach of death. In “This Life,” a setting of Cohen’s poem “Mission” she sings:

My longing’s a place

my dying a sail.

It’s pretty clear that Cohen is a real touchstone and inspiration to Souza; she also set two of his poems to her music on her previous album, Speaking In Tongues. All the more incredible when you consider that all the rest of the album is comprised of wordless compositions, with Souza doing vocalese as part of the musical ensemble

Life is about longing, a lengthy sigh, and death is the sail that sets us free of that longing. We live temporally because of our mortality, and we populate our world with our own beliefs about how it is. The material concern of Souza’s opener, “These Things” is followed by “Daybreak,” which is a hymn to the eternal, to the things that seem changeless to us (though they are not) because they outlast the arc of our lives:

water, snow

oceans flow

peace, battles

stay, go

The Book of Longing is a group of songs about our lives, about the things that happen to us, to all of us, and the things that ultimately matter. The sound is intimate and warm, and it pulls you in like a whisper. It’s as though Souza and her musicians were sitting in your living room, not so much giving a performance as engaging in conversation.