Approximately Infinite Universe

Approximately Infinite Universe is a trojan horse: it affects the sound of hip youth culture of the time in order to pass an ideological message to its listeners. The message was received as evidenced by the many indie and alt-rock female artists who appeared shortly after as part of the punk rock movement and through the 1990s and 2000s.

It was also received by the mainstream, and the mainstream did not like the message that Ono was preaching. She was used to the sexist and racist jokes and comments that followed in the wake of her appearance around the periphery of an already dying Beatles and her subsequent artistic escapades with Lennon. She’d also dealt with the sexism and misogyny of the avant-garde art world, an academic world ruled by men who were unlikely to acknowledge the seriousness of any female artist’s work.

But it’s difficult to comprehend the vicious nature of these attacks. For example, Esquire, a very mainstream publication, published an article about Yoko based on an interview done when she and Lennon were living in California that was titled “John Rennon’s Excrusive Gloupie.” Or the disgraceful Rolling Stone review of Approximately Infinite Universe by Nick Tosches that doesn’t address the record itself:

“What does any of this have to do with the universe? Since when does the staggering, ever-expanding universe have anything to do with some rich kid sniveling about the turmoil within her run-of-the-mill soul or crooning philosophical and political party-line corn that went out of style with last season’s prime-time TV?

And it’s not just me. I know a guy who’s in the forefront of the avant-garde and he doesn’t like it either.”

Nick Tosches, Review of Approximately Infinite Universe, Rolling Stone, March 15, 1973

Well, duh. Yoko’s currency with serious, mostly white, male avant-garde artists and critics was shot once she started recording and performing with Lennon, and a serious record of rock songs was unlikely to change their minds.

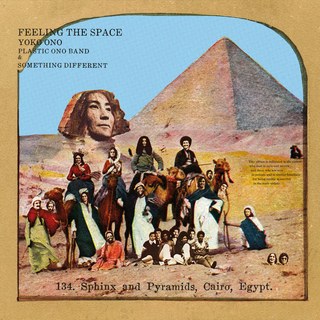

Feeling the Space

Feeling the Space sounds mellower and more relaxed than much of Approximately Infinite Universe, but Ono doubles down on her feminist viewpoint and represents a persona that sounds, in many ways, angrier or at least more frustrated. However, the music, played by a coterie of exceptional studio musicians (David Spinozza, Ken Ascher, Jim Keltner, Michael Brecker, Sneaky Pete Kleinow, and many more) is more tranquil and flawless than ever.

Ono sticks close to the theme of women’s oppression at the hands of men and exhortations to her fellow women to rise up and take control of their own lives, but her presentation is such that it’s easy to be drawn in before getting the full message like a punch in the face. Songs like the opening “Growing Pain,” “Coffin Car,” and “Run, Run, Run” go over easily, paving the way for more dramatic fare, such as “Woman of Salem.” The song invokes the Salem witch trials as part of the oppression of women and reclaiming the word ‘witch’ was a part of many feminists’ agendas. Ono paints Salem like something out of The Handmaid’s Tale:

Let my daughter burn my book,

Let her learn to sew and cook.

Teach her not to read but weave,

Ask her not to speak but weep.

Having professional musicians backing her in place of an actual band is a double-edged sword. It no doubt got more people to listen to Feeling the Space than had checked out Fly or Plastic Ono Band. But the cognitive dissonance between the straightforward 70s rock and Ono’s message and delivery is, at times, really hard to reconcile.

Although John Lennon is credited as co-producer and as a guitarist (he did play some solos), I’ve seen multiple sources state that he was not around much during the sessions for Feeling the Space and that it was Ono’s first self-produced album.

It makes sense, as he was preoccupied with appealing his immigration status as he’d been ordered to leave the country. In addition, John and Yoko’s relationship was in a very tumultuous phase. That may well have contributed to the harder-edged lyrics on Feeling the Space as well as to Lennon being less present. As soon as Ono had finished recording Feeling the Space, Lennon booked the same band to record his Mind Games album. By the time both albums were released John and Yoko had begun a separation that would last 18 months.

Ono’s dedication reads “This album is dedicated to the sisters who died in pain and sorrow and those who are now in prisons and in mental hospitals for being unable to survive in the male society.” Keeping her narrative personal helps push Yoko’s message and allows one to sit through some of the preachier cuts. Just as on Universe’s “Death of Samantha” the woman in “Coffin Car” walking around as if she is already dead, is startlingly familiar. The protagonist of “Angry Young Woman” has left her husband and children for an uncertain but independent life. Still, she “thinks of the first Sundays they spent at the park.”

How personal are these songs? In a live performance in 1973 at the Feminist Planning Conference Ono introduced a performance of “Coffin Car” with the following monologue:

“…I was living as an artist and had relative freedom as a woman and was considered a bitch in this society. Since I met John, I was upgraded into a witch and I think that that’s very flattering.

Anyway, what I learned from being with John is that society suddenly treated me as a woman…who belonged to a man who is one of the most powerful people in our generation. Some of his closest friends told me that probably I should stay in the background, I should shut up. I should give up my work and that way I’d be happy.

I was lucky. I was over 30 and it was too late for me to change. But still… I want to say this to the sisters because I really wish that you know that you are not alone.

Because the whole society started to attack me and the whole society wished me dead, I started to accumulate a tremendous amount of complex and as a result of that, I started to stutter.

I consider myself a very elegant and also an attractive woman, all my life and suddenly because I was associated with John I was considered an ugly woman, ugly Jap who took your monument or something away from you.

That’s when I realized how hard it is for women. If I can start to stutter being a strong woman, and having lived 30 years by then, learn to stutter in 3 years being treated as such, it is a very hard road.”

Yoko ono, “I Began to stutter/coffin car’, released on onobox, 1972

Feeling the Space was first planned as a double album, but that was changed in part because Approximately Inifinite Universe hadn’t done well enough and the fact that Apple Records wasn’t doing that well. Another album, A Story, was planned for 1974 containing some of the leftover tracks from Feeling the Space and some new material, but it never materialized.

After Feeling the Space

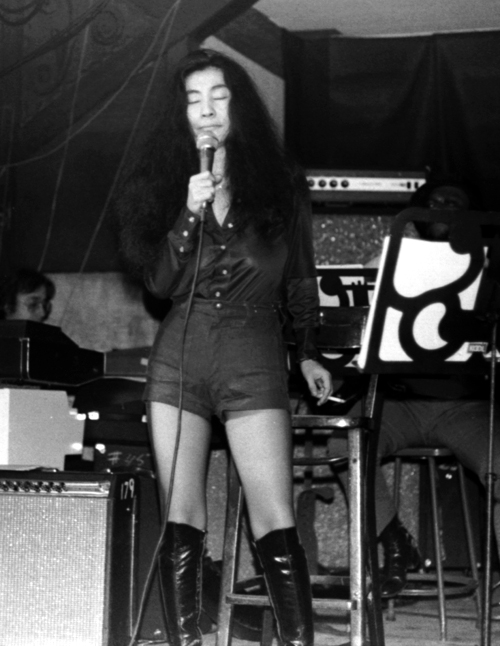

In October of 1973, Yoko Ono played live for a week at Kenny’s Castaways on 84th Street with a band billed as the Plastic Ono Super Band. Her reviews were uniformly bad, with Melody Maker’s Vicki Wickham stating “I still haven’t figured out what is “inside” everyone that makes them not only want to sing, but to so firmly believe they can sing!” An equally devastating but more insightful observation was written by the NY Times’ John Rockwell. He declaims that Ono is “a simply terrible pop music performer” then goes on:

“Yet it can’t be that simple. Miss Ono is certainly not dumb. Surely she must realize that by any normal criterion she is terrible; in fact, she deliberately emphasizes the abrasive aspects of her singing. So what is she up to? …Her whole performance Tuesday, seemed designed to provoke an awareness of contradictions—particularly the oddity of her persistent concern with women’s integrity coupled with a costume, that included hot pants and black plastic boots up to her knees. But at the moment the means by which she confronts her audience are so grating that few will be willing to put up with her for long.”

John ROckwell, ‘Yoko Ono’s Contradictions’, New York Times, October 26, 1973

It does seem clear that Yoko Ono enjoys playing with contractions, finding the areas of discomfort in our lives, whether it’s our relationships with each other or the theatrical spectacle of pop music. In this regard, she is always ‘feeling the space’ where things are and how far that space can be expanded, how far boundaries can be pushed. That she was ahead of the culture is readily demonstrated by Rockwell’s comments that conflate what a woman wears and how she chooses to present herself with her message.

There was no followup to Feeling the Space. The 1992 release Onobox, a six-CD boxed set, contains the entire group of songs meant to comprise the double album version of Feeling the Space as well as the entire 1974 planned release A Story.

Yoko Ono was not heard from as a popular music performer until the release of 1980’s Double Fantasy, a collaboration with Lennon that was his last. Ono followed up with the strong album Season of Glass in 1981 and thereafter has recorded new music periodically.